PrEP Provider Toolkit

Uplifting BIPOC for PrEP Uptake

Barriers to PrEP Faced by Communities Disproportionately Impacted by HIV

While African Americans only make up 13% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 42% of the 37,832 new HIV diagnoses in 2018, the highest rate among all racial and ethnic groups. Black women accounted for 57% of the new HIV diagnoses among women. Most new HIV diagnoses among women are attributed to heterosexual contact (84%) followed by injection drug use (16%). Black/African American cisgender women continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. Challenges to successful PrEP implementation among ciswomen include lack of awareness, access to healthcare, insurance and out-of-pocket costs and low perceived risk.

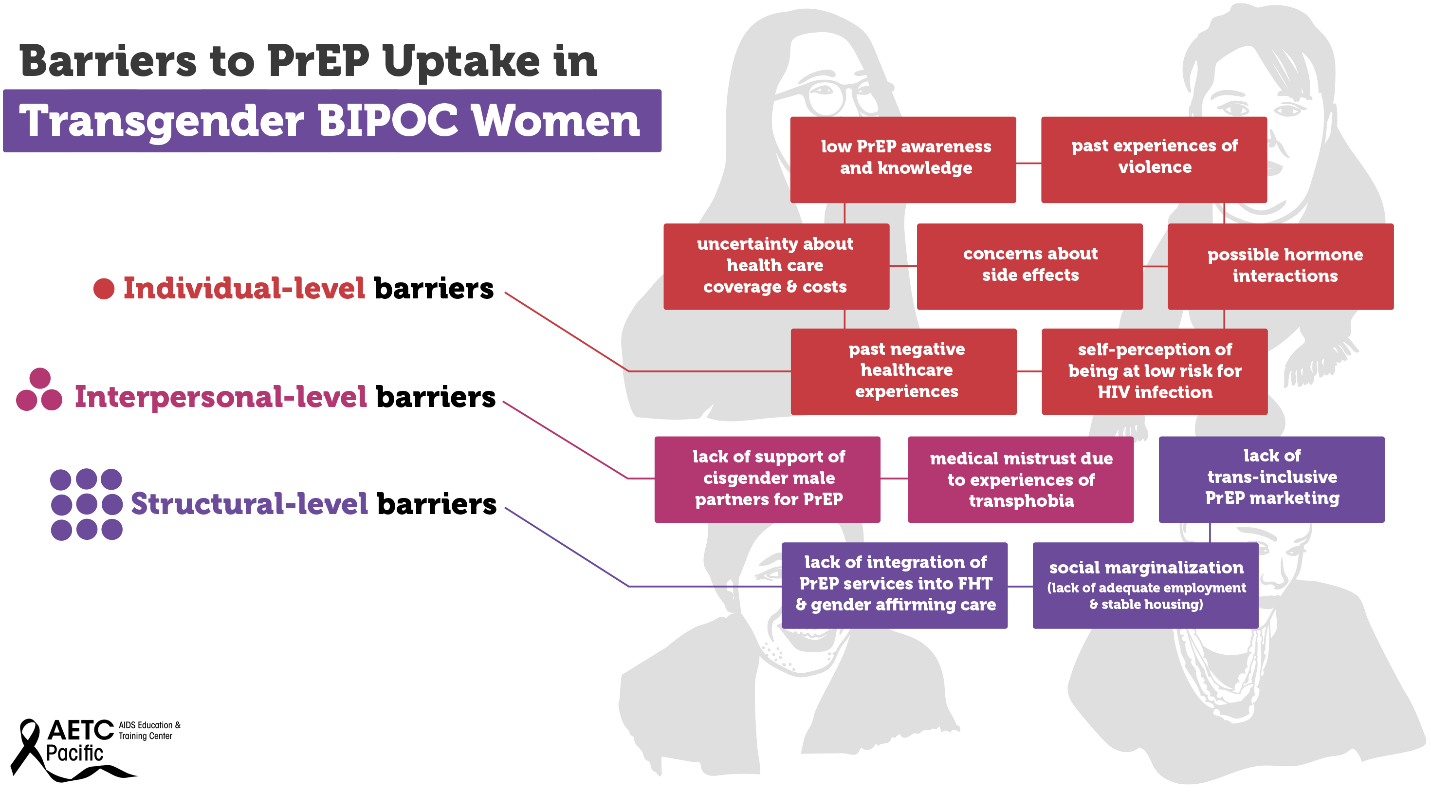

Transgender women—those who were assigned male at birth and who identity as female—are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the U.S. Between 2009 and 2014, an estimated 1,974 transgender women were diagnosed with HIV in the U.S., representing 84% of transgender people diagnosed. Racial and ethnic minority transgender women bear a higher burden of HIV compared to White transgender women. In the U.S., an estimated 44% of Black transgender women and 26% of Hispanic/Latina transgender women are living with HIV compared to 7% of White transgender women. Barriers to PrEP uptake among transgender women fall along multiple socio-ecological levels. Individual-level barriers may include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

Some examples of interpersonal-level barriers include lack of support of cisgender male partners for PrEP, and medical mistrust due to experiences of transphobia. Structural-level barriers include lack of trans-inclusive PrEP marketing, lack of integration of PrEP services into feminizing hormone therapy (FHT) and gender affirming care, and social marginalization (lack of adequate employment and stable housing). Experiences of social marginalization because of gender, class, race, sexual identity, poverty, and the intersection of these identities and experiences may contribute to increased vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Hispanic/Latina transgender women. Although several studies have investigated barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake among transgender women, there is a dearth of research on multilevel barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence specifically among Black and Hispanic/Latinx transgender women.

>

In the United States, Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) are the most affected by HIV and are diagnosed at a rate of 6.0 times higher than white MSM. Awareness and uptake of PrEP are lowest among this community. Latino MSM are another group that is critically affected by HIV and account for 85% of all new HIV diagnoses among Latino males. Like BMSM, barriers like cost and lack of insurance, concerns about side effects, societal or contextual factors such as racism and homophobia and HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs are barriers preventing Latino MSM from accessing PrEP.

Youth continue to be a population impacted by higher rates of HIV. In 2019, 21% of new HIV diagnoses were among young people aged 13-24, and most of these cases are among Black and Latino youth. PrEP uptake among racial and ethnic minority adolescents has been slow due to lack of awareness of PrEP, behavioral factors, and legal and financial barriers to adolescents seeking sexual and reproductive health care.

Indian/Alaska Native adults and adolescents increased. Access to PrEP and PEP in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities can be limited and there are cultural and historical considerations that impact Tribal communities’ ability to adopt PrEP, and social and systematic considerations that also present challenges.

According to the CDC, Asian Americans who make up only 6 percent of the U.S. population, make up 2 percent of all HIV infections. The CDC suggests this disparity is so great due to cultural factors, such as language barriers and immigration issues that create barriers to accessing healthcare (though this only addresses access to care for Asian immigrants, not Asian Americans who have lived in the U.S. for generations.) Low PrEP utilization rates among the Asian/Pacific Islander communities could be because of lack of awareness about the medication, misconceptions regarding its affordability, misinformation about its effects and fear of community stigma about sex.

HIV incidence is high among people who use drugs and are unhoused across the U.S. This is fueled by the opioid epidemic, lack of affordable housing, socioeconomic marginalization, and other complex factors. Despite this, PrEP is largely under-utilized among this vulnerable population.

Some of the low PrEP uptake can be attributed to practical barriers, such as competing health and survival needs, and medications being lost or stolen due to being unhoused and without a safe place to store medications. However, there is also a pervasive belief among clinicians that people who use drugs who are unhoused are not good candidates for PrEP. This idea is likely due to overlapping stigmas and isn’t supported by data.

According to California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS, Substance Use Community engagement efforts have linked methamphetamine use to increased risk for HIV infection and falling out of medical care. County-specific data on methamphetamine use is not easily accessible. This CDPH report on Ending the HIV Epidemic utilizes county-specific data on 1) amphetamine-related Emergency Department (ED) visits and 2) amphetamine-related deaths 2011-2018; all data obtained from the California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard. From 2011-2013, there was an overall increase of ED visits attributable to amphetamine use in Alameda County, from 5.01 visits/100,000 population in 2011, to 5.81/100,000 in 2013. Since 2013, ED visits steadily declined to a low of 1.7/100,000 in 2018. Deaths, on the other hand, fluctuated more widely, from a low of 1.18/100,000 in 2011 to a high of 4/100,000 in 2013.

However, in 2018, deaths attributable to amphetamine use spiked dramatically to a high of 8.26/100,000. This spike, coming as ED visits continued to decline, may reflect persons not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose rather than decreased use. Not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose could be secondary to a lack of access to medical care, fear of legal ramifications, or to unwitnessed overdose— the reasons are unclear from this data.