PrEP Provider Toolkit

Uplifting BIPOC for PrEP Uptake

Why Are We Doing So Poorly?

National HIV screening recommendations place healthcare providers at the helm in the fight against HIV. While the goal of healthcare providers should be to ensure high quality HIV prevention for patients, their stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward vulnerable populations impede progress in identifying patients who would benefit from PrEP. Some of the assumptions that clinicians make about patients seeking PrEP accompany and may exacerbate systemic factors affecting PrEP uptake, like patients’ distrust, lack of access to care, and lack of awareness of PrEP. One of the key reasons cited for clinicians not prescribing PrEP is their assumption that patients will not be adherent to PrEP followed by assumptions that patients taking PrEP will increase their frequency of condomless sex or number of sexual partners.

What is Medical Mistrust?

Medical Mistrust is “an absence of trust that health care providers and organizations genuinely care for patients’ interests, are honest, practice confidentiality, and have the competence to produce the best possible results.”

The Origins of Medical Mistrust

Research indicates that Medical Mistrust is rooted in the history of mistreatment, discrimination, and abuse perpetrated against Black and brown bodies, sexual and gender diverse people, and other marginalized groups by both the State and the medical establishment. In addition, contemporary experiences of discrimination in health such as inequities in access to medical insurance, health care facilities, and treatments along with institutional practices that make it difficult for marginalized communities to access quality health care also play a significant role in shaping Medical Mistrust particularly among Black and other patients of color. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

The Impact of Medical Mistrust

- Trust in health care among Americans has declined in recent decades

- Mistrust may prevent people from seeking care

- Black Americans are more likely than whites to say they do not trust their medical provider

- People who say they mistrust health care organizations are less likely to take medical advice, keep follow-up appointments, or fill prescriptions

- People who say they mistrust health care systems are more likely to report being in poor health

Talking with Patients about Medical Mistrust – How to Have Those Conversations

In the U.S., trust in the health care system is extremely low. Reversing medical mistrust is integral to building and strengthening patient-provider relationships. Health care professionals should assume patient mistrust and take the appropriate steps to address it.

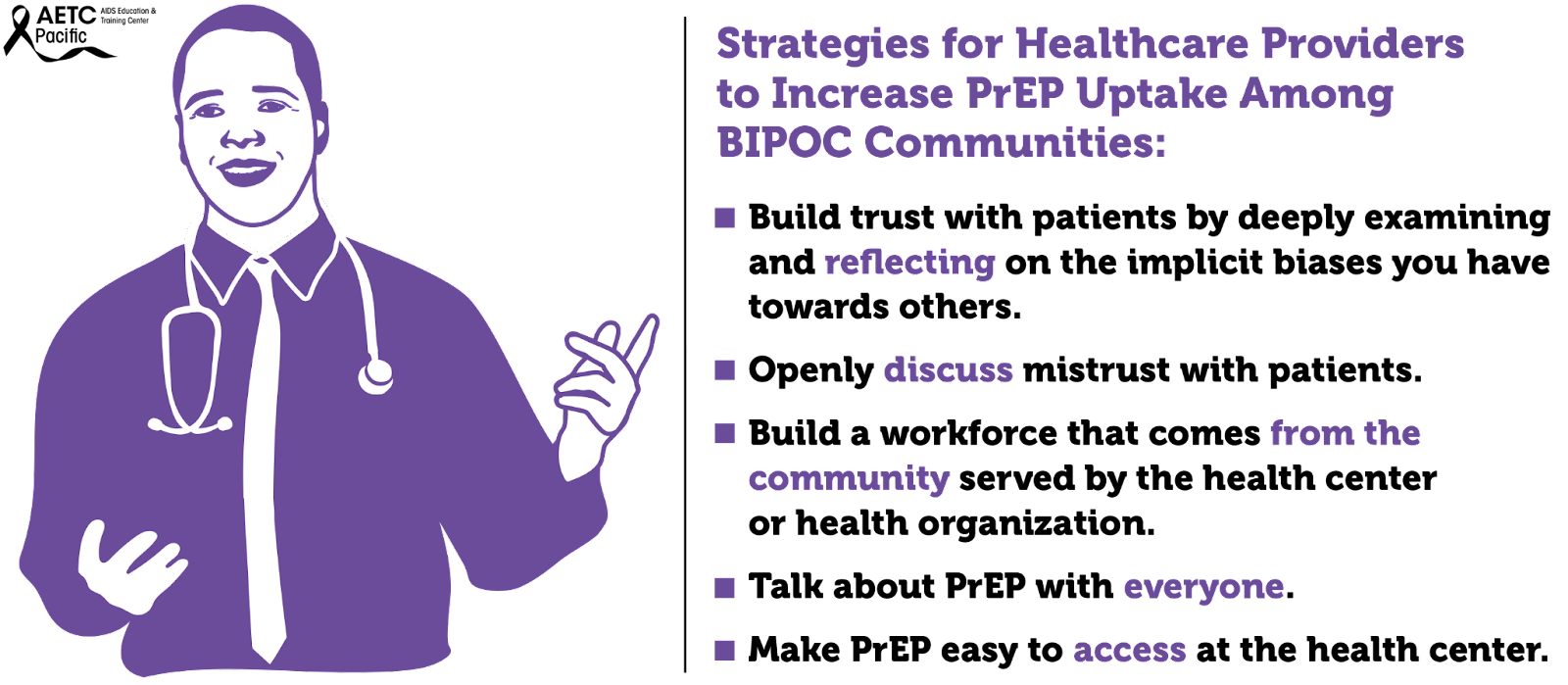

Effective ways to communicate with patients about Medical Mistrust

- Openly discuss mistrust with patients

- Talk with, not at patients

- Partner with patients in making decisions about their health care

Medical mistrust has been identified as a primary driver of racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes in the U.S. Among Black individuals, medical mistrust stems from experiences with discrimination in healthcare and is the result of persistent social inequity and structural racism, both contemporary and historical. Regarding PrEP use, several studies have identified medical mistrust as a barrier to uptake among Black individuals. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

Medical mistrust is a major barrier to a strong patient-clinician relationship. Patient mistrust in health care clinicians and in the health care system generally, negatively influences patient behavior and health outcomes.

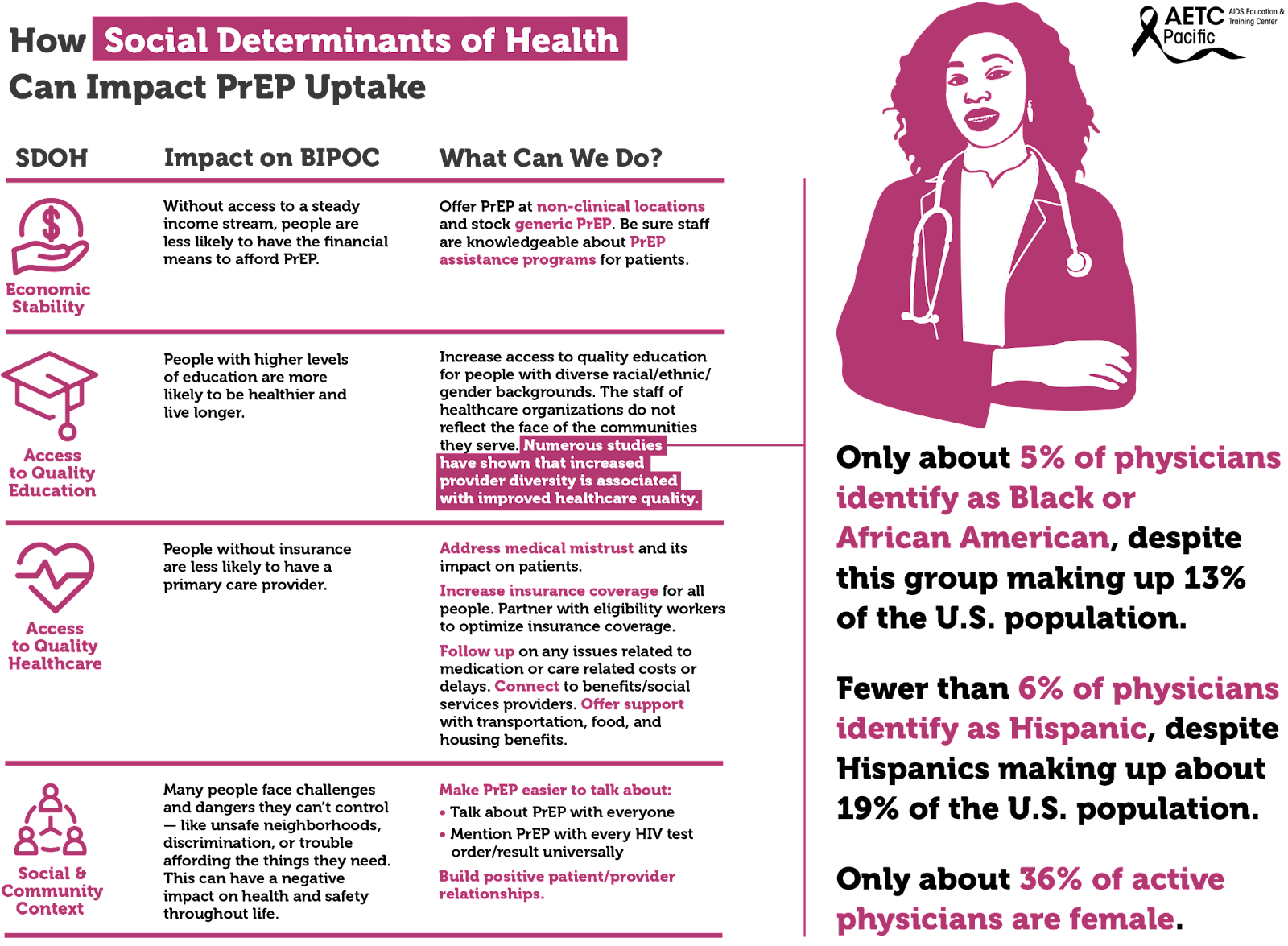

Furthermore, the staff of healthcare organizations do not reflect the face of the communities they serve. Numerous studies have shown that increased provider diversity is associated with improved healthcare quality. Concordant care, defined as a patient and provider sharing a common attribute such as race, ethnicity, or gender, has been associated with improved quality of care. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, only about 36% of active physicians are female, and only about 5% of physicians identify as Black or African-American, despite this group making up 13% of the U.S. population. Fewer than 6% of physicians identify as Hispanic, despite Hispanics making up about 19% of the U.S. population. However, 28% of physicians and surgeons in the United States are immigrants, with doctors from India and China making up the largest groups. This speaks to issues of systemic oppression: People from minority groups that have been oppressed for generations in the United States are less represented as physicians than are immigrants of color. There is a long history related to how we have gotten here. Since Abraham Flexner’s review of the American medical education system in 1910, it was believed that there was a limited role for Black physicians in the medical community and that Black physicians possessed less potential and ability than their White counterparts. The result of this characterization led to the closure of five of seven African American medical schools. The impact is still felt today.

Social determinants of health, the conditions in environments where people live, drive inequities, HIV acquisition and the use of PrEP among BIPOC. These social determinants include, among others, economic stability, access to quality education, and access to quality healthcare.

The uptake of PrEP has been shown to be impacted by unmet social determinants of health (SDOH) needs. These include basic needs (e.g., food, shelter, water), health/social service needs (e.g., healthcare), and economic needs (e.g., money for savings). Socioeconomic factors identified to affect PrEP uptake included lack of insurance, difficult access to transportation, and inflexible work situations. Individuals with more unmet SDOH needs may have other priorities that divert their focus from obtaining preventative health services.

There are multiple socioeconomic factors to consider when looking at the barriers to PrEP uptake among disproportionately impacted communities at both the individual-level and structural-level barriers. Individual-level barriers to PrEP uptake include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.