PrEP Provider Toolkit

Uplifting BIPOC for PrEP Uptake

- Providing PrEP to BIPOC

- Barriers to PrEP Faced by

Communities Disproportionately Impacted by HIV - Why Are We Doing So Poorly?

- What providers can do to

improvePrEP utilization

among BIPOC people?

Providing PrEP to BIPOC

The BIPOC acronym stands for Black, Indigenous and People of Color. The term BIPOC is used to highlight the unique relationship to whiteness that Indigenous and Black people have that shapes the experiences of and relationship to white supremacy for all people of color within a U.S. context. Using the term BIPOC is people-first and allows us to shift away from terms like “marginalized” and “minority.”

Structural and political determinants of health drive inequities, HIV infection and the use of PrEP among BIPOC. In 2018, at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) new data about PrEP use showed that PrEP medication is not reaching most Americans who could benefit, especially people of color. Out of 500,000 African Americans and nearly 300,000 Latinos across the nation that could benefit from PrEP only 7,000 prescriptions were filled by these communities. This data shows a stark unmet need for HIV prevention medication.

Longstanding social and economic inequities elevate health risks and vulnerabilities for BIPOC, and HIV continues to disproportionately impact these communities, specifically sexual minority men and transgender women in the United States. Disparities are most prominent for Black and Hispanic/Latino groups. At the current rate of infection, estimates suggest that 1 in 2 Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and 1 in 5 Hispanic/Latino MSM will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime; these racial and ethnic disparities in HIV prevalence also extend to Black and Hispanic/Latina transgender women. These communities carry a higher burden of HIV compared to white transgender women. In the U.S., an estimated 44% of Black and 26% of Latino/Hispanic transgender women are living with HIV compared to 7% of white transgender women. The substantial disparity of HIV in these communities is driven by experiences of discrimination and stigma, lack of access to healthcare services, lack of education and employment opportunities, and unstable housing.

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) inequities in the US – both in terms of race and geographical location – have not only persisted in the last decade, but have increased, according to research presented to the 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022) by Dr Patrick Sullivan from Emory University.

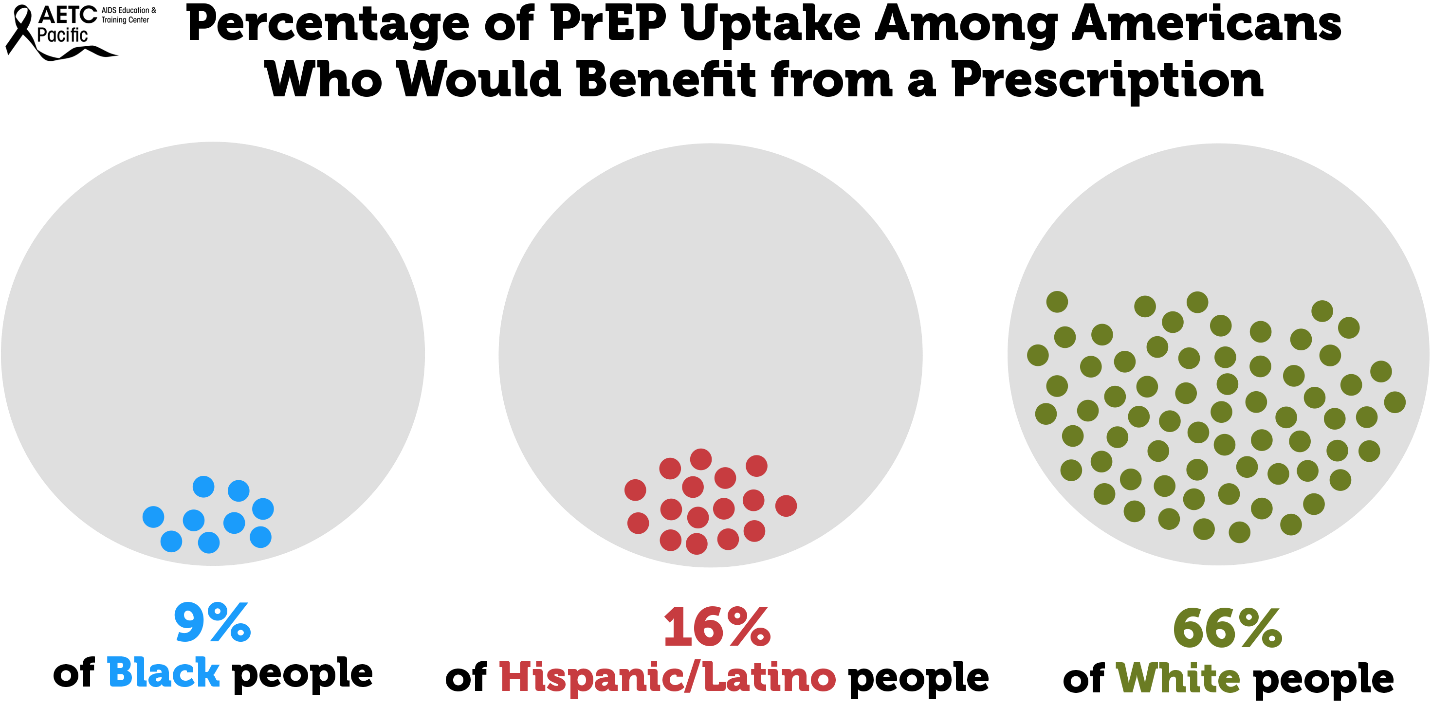

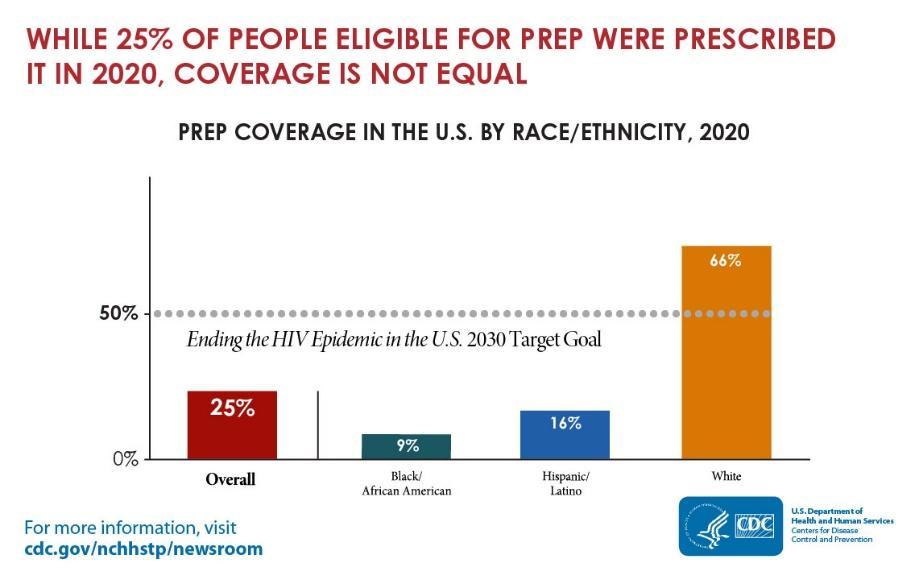

While HIV prevention methods, such as PrEP, are highly effective and necessary in ending the HIV epidemic, serious racial/ethnic disparities, structural inequities, and systemic racism block progress for Black and Hispanic/Latino cis-gender sexual minority men and transgender women in accessing this effective HIV prevention medication. In 2018, at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), new data about PrEP use showed that PrEP medication is not reaching most Americans who could benefit, especially people of color. PrEP uptake has been persistently low among US women, particularly Black cisgender women, who account for 61% of new HIV diagnoses among cis women. Preliminary 2020 CDC data show only 9% (42,372) of the nearly 469,000 Black people who could benefit from PrEP received a prescription in 2020, and only 16% (48,838) of the nearly 313,000 Hispanic/Latino people who could benefit from PrEP received a prescription. Meanwhile, 66% of their White counterparts are utilizing PrEP. This emphasizes the continued unmet need for HIV prevention medication, especially among BIPOC.

Barriers to PrEP Faced by Communities Disproportionately Impacted by HIV

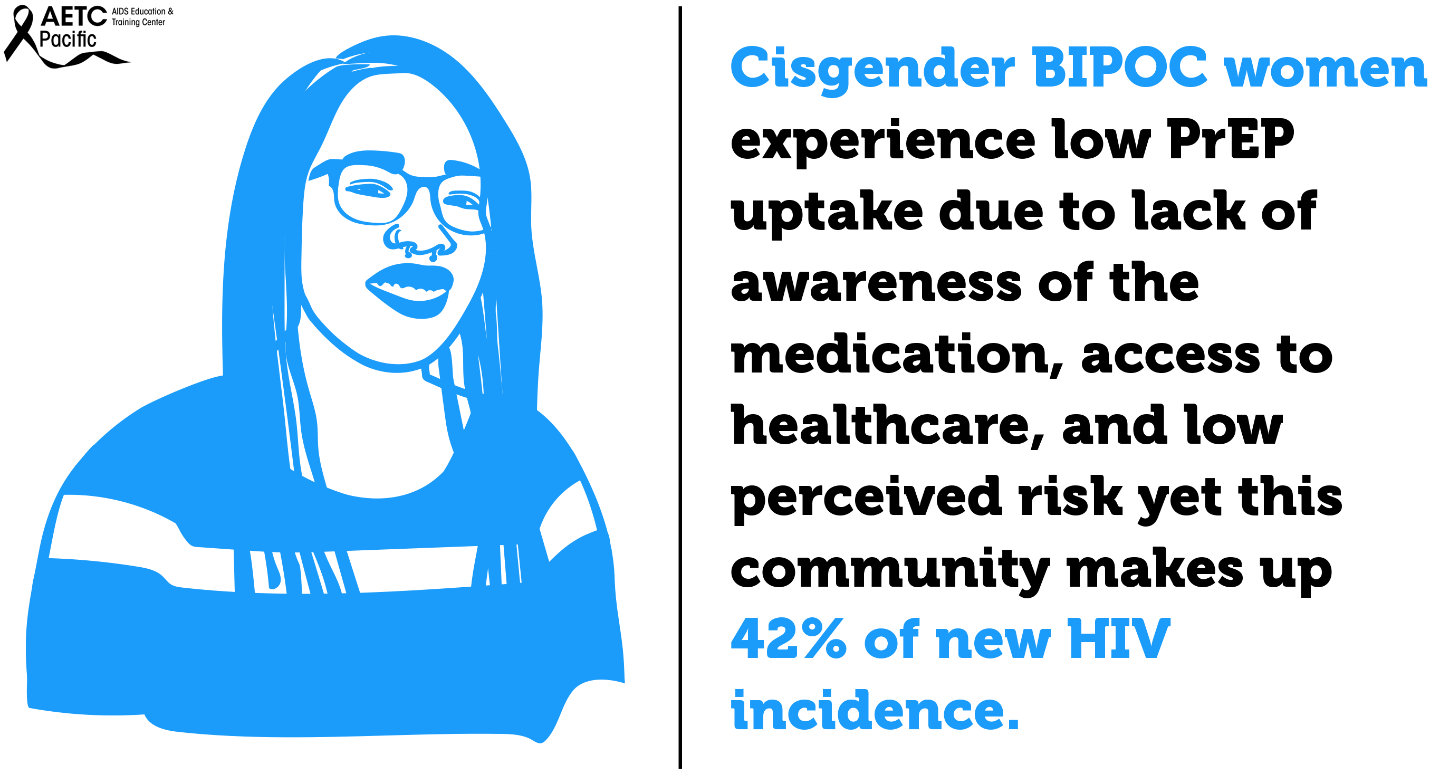

While African Americans only make up 13% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 42% of the 37,832 new HIV diagnoses in 2018, the highest rate among all racial and ethnic groups. Black women accounted for 57% of the new HIV diagnoses among women. Most new HIV diagnoses among women are attributed to heterosexual contact (84%) followed by injection drug use (16%). Black/African American cisgender women continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. Challenges to successful PrEP implementation among ciswomen include lack of awareness, access to healthcare, insurance and out-of-pocket costs and low perceived risk.

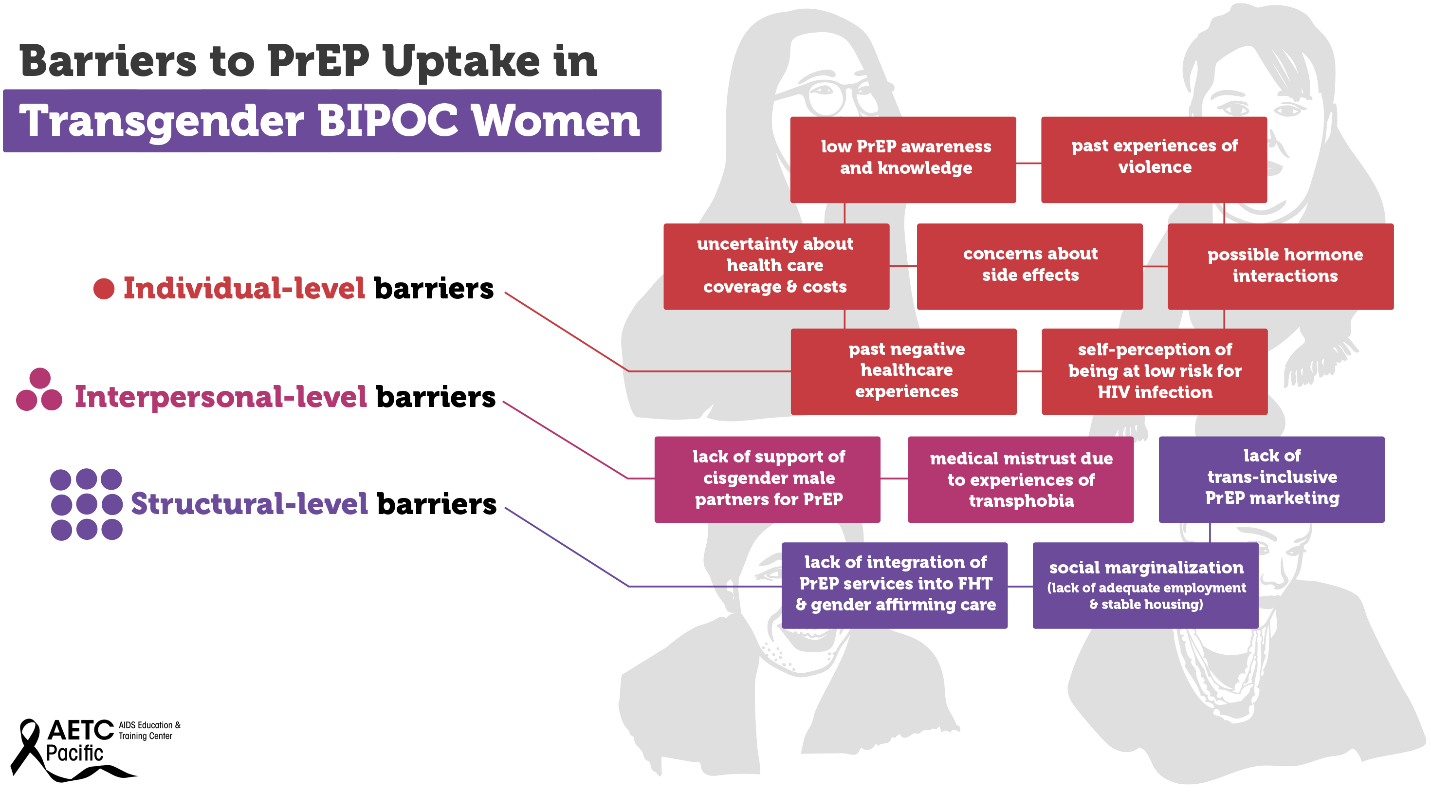

Transgender women—those who were assigned male at birth and who identity as female—are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the U.S. Between 2009 and 2014, an estimated 1,974 transgender women were diagnosed with HIV in the U.S., representing 84% of transgender people diagnosed. Racial and ethnic minority transgender women bear a higher burden of HIV compared to White transgender women. In the U.S., an estimated 44% of Black transgender women and 26% of Hispanic/Latina transgender women are living with HIV compared to 7% of White transgender women. Barriers to PrEP uptake among transgender women fall along multiple socio-ecological levels. Individual-level barriers may include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

Some examples of interpersonal-level barriers include lack of support of cisgender male partners for PrEP, and medical mistrust due to experiences of transphobia. Structural-level barriers include lack of trans-inclusive PrEP marketing, lack of integration of PrEP services into feminizing hormone therapy (FHT) and gender affirming care, and social marginalization (lack of adequate employment and stable housing). Experiences of social marginalization because of gender, class, race, sexual identity, poverty, and the intersection of these identities and experiences may contribute to increased vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Hispanic/Latina transgender women. Although several studies have investigated barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake among transgender women, there is a dearth of research on multilevel barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence specifically among Black and Hispanic/Latinx transgender women.

>

In the United States, Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) are the most affected by HIV and are diagnosed at a rate of 6.0 times higher than white MSM. Awareness and uptake of PrEP are lowest among this community. Latino MSM are another group that is critically affected by HIV and account for 85% of all new HIV diagnoses among Latino males. Like BMSM, barriers like cost and lack of insurance, concerns about side effects, societal or contextual factors such as racism and homophobia and HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs are barriers preventing Latino MSM from accessing PrEP.

Youth continue to be a population impacted by higher rates of HIV. In 2019, 21% of new HIV diagnoses were among young people aged 13-24, and most of these cases are among Black and Latino youth. PrEP uptake among racial and ethnic minority adolescents has been slow due to lack of awareness of PrEP, behavioral factors, and legal and financial barriers to adolescents seeking sexual and reproductive health care.

Indian/Alaska Native adults and adolescents increased. Access to PrEP and PEP in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities can be limited and there are cultural and historical considerations that impact Tribal communities’ ability to adopt PrEP, and social and systematic considerations that also present challenges.

According to the CDC, Asian Americans who make up only 6 percent of the U.S. population, make up 2 percent of all HIV infections. The CDC suggests this disparity is so great due to cultural factors, such as language barriers and immigration issues that create barriers to accessing healthcare (though this only addresses access to care for Asian immigrants, not Asian Americans who have lived in the U.S. for generations.) Low PrEP utilization rates among the Asian/Pacific Islander communities could be because of lack of awareness about the medication, misconceptions regarding its affordability, misinformation about its effects and fear of community stigma about sex.

HIV incidence is high among people who use drugs and are unhoused across the U.S. This is fueled by the opioid epidemic, lack of affordable housing, socioeconomic marginalization, and other complex factors. Despite this, PrEP is largely under-utilized among this vulnerable population.

Some of the low PrEP uptake can be attributed to practical barriers, such as competing health and survival needs, and medications being lost or stolen due to being unhoused and without a safe place to store medications. However, there is also a pervasive belief among clinicians that people who use drugs who are unhoused are not good candidates for PrEP. This idea is likely due to overlapping stigmas and isn’t supported by data.

According to California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS, Substance Use Community engagement efforts have linked methamphetamine use to increased risk for HIV infection and falling out of medical care. County-specific data on methamphetamine use is not easily accessible. This CDPH report on Ending the HIV Epidemic utilizes county-specific data on 1) amphetamine-related Emergency Department (ED) visits and 2) amphetamine-related deaths 2011-2018; all data obtained from the California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard. From 2011-2013, there was an overall increase of ED visits attributable to amphetamine use in Alameda County, from 5.01 visits/100,000 population in 2011, to 5.81/100,000 in 2013. Since 2013, ED visits steadily declined to a low of 1.7/100,000 in 2018. Deaths, on the other hand, fluctuated more widely, from a low of 1.18/100,000 in 2011 to a high of 4/100,000 in 2013.

However, in 2018, deaths attributable to amphetamine use spiked dramatically to a high of 8.26/100,000. This spike, coming as ED visits continued to decline, may reflect persons not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose rather than decreased use. Not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose could be secondary to a lack of access to medical care, fear of legal ramifications, or to unwitnessed overdose— the reasons are unclear from this data.

Why Are We Doing So Poorly?

National HIV screening recommendations place healthcare providers at the helm in the fight against HIV. While the goal of healthcare providers should be to ensure high quality HIV prevention for patients, their stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward vulnerable populations impede progress in identifying patients who would benefit from PrEP. Some of the assumptions that clinicians make about patients seeking PrEP accompany and may exacerbate systemic factors affecting PrEP uptake, like patients’ distrust, lack of access to care, and lack of awareness of PrEP. One of the key reasons cited for clinicians not prescribing PrEP is their assumption that patients will not be adherent to PrEP followed by assumptions that patients taking PrEP will increase their frequency of condomless sex or number of sexual partners.

What is Medical Mistrust?

Medical Mistrust is “an absence of trust that health care providers and organizations genuinely care for patients’ interests, are honest, practice confidentiality, and have the competence to produce the best possible results.”

The Origins of Medical Mistrust

Research indicates that Medical Mistrust is rooted in the history of mistreatment, discrimination, and abuse perpetrated against Black and brown bodies, sexual and gender diverse people, and other marginalized groups by both the State and the medical establishment. In addition, contemporary experiences of discrimination in health such as inequities in access to medical insurance, health care facilities, and treatments along with institutional practices that make it difficult for marginalized communities to access quality health care also play a significant role in shaping Medical Mistrust particularly among Black and other patients of color. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

The Impact of Medical Mistrust

- Trust in health care among Americans has declined in recent decades

- Mistrust may prevent people from seeking care

- Black Americans are more likely than whites to say they do not trust their medical provider

- People who say they mistrust health care organizations are less likely to take medical advice, keep follow-up appointments, or fill prescriptions

- People who say they mistrust health care systems are more likely to report being in poor health

Talking with Patients about Medical Mistrust – How to Have Those Conversations

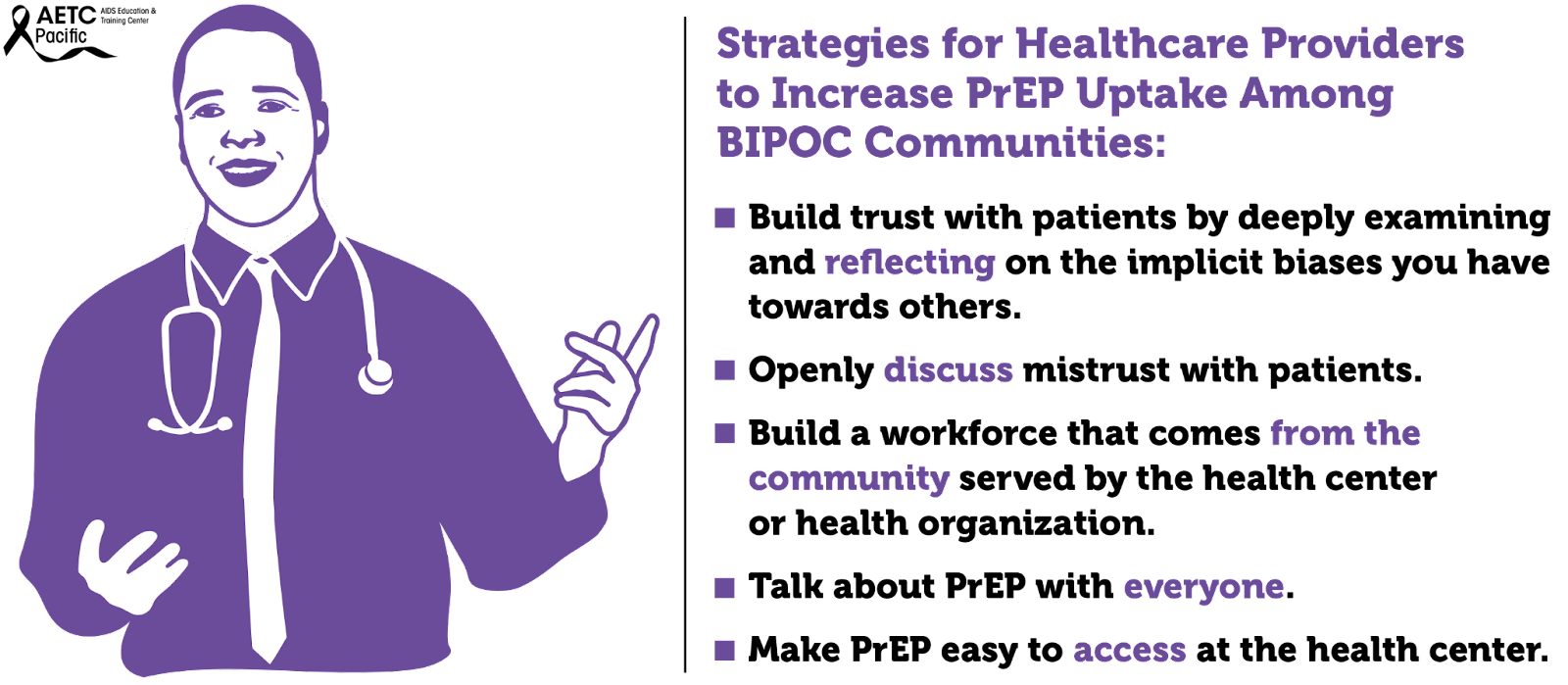

In the U.S., trust in the health care system is extremely low. Reversing medical mistrust is integral to building and strengthening patient-provider relationships. Health care professionals should assume patient mistrust and take the appropriate steps to address it.

Effective ways to communicate with patients about Medical Mistrust

- Openly discuss mistrust with patients

- Talk with, not at patients

- Partner with patients in making decisions about their health care

Medical mistrust has been identified as a primary driver of racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes in the U.S. Among Black individuals, medical mistrust stems from experiences with discrimination in healthcare and is the result of persistent social inequity and structural racism, both contemporary and historical. Regarding PrEP use, several studies have identified medical mistrust as a barrier to uptake among Black individuals. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

Medical mistrust is a major barrier to a strong patient-clinician relationship. Patient mistrust in health care clinicians and in the health care system generally, negatively influences patient behavior and health outcomes.

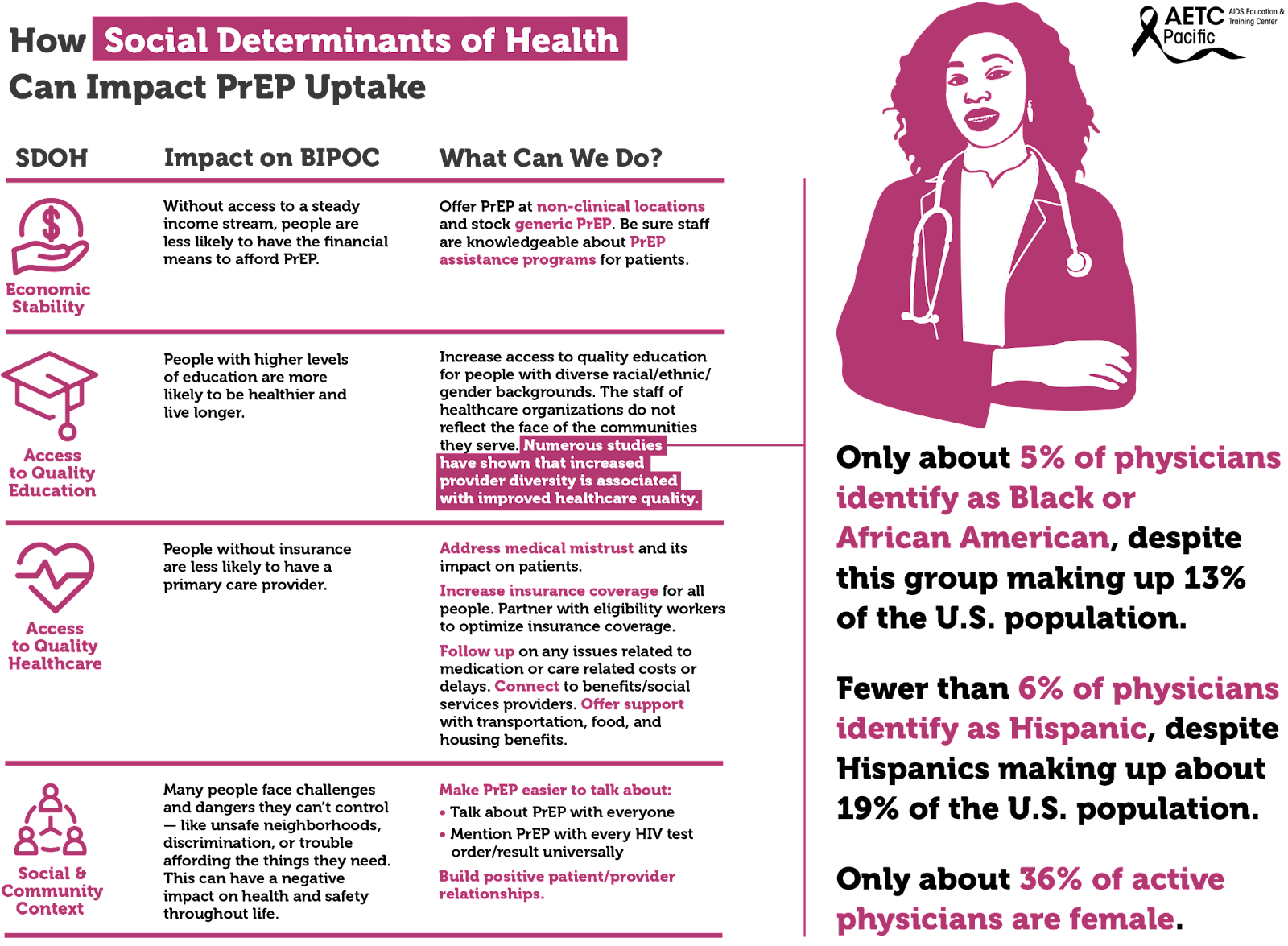

Furthermore, the staff of healthcare organizations do not reflect the face of the communities they serve. Numerous studies have shown that increased provider diversity is associated with improved healthcare quality. Concordant care, defined as a patient and provider sharing a common attribute such as race, ethnicity, or gender, has been associated with improved quality of care. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, only about 36% of active physicians are female, and only about 5% of physicians identify as Black or African-American, despite this group making up 13% of the U.S. population. Fewer than 6% of physicians identify as Hispanic, despite Hispanics making up about 19% of the U.S. population. However, 28% of physicians and surgeons in the United States are immigrants, with doctors from India and China making up the largest groups. This speaks to issues of systemic oppression: People from minority groups that have been oppressed for generations in the United States are less represented as physicians than are immigrants of color. There is a long history related to how we have gotten here. Since Abraham Flexner’s review of the American medical education system in 1910, it was believed that there was a limited role for Black physicians in the medical community and that Black physicians possessed less potential and ability than their White counterparts. The result of this characterization led to the closure of five of seven African American medical schools. The impact is still felt today.

Social determinants of health, the conditions in environments where people live, drive inequities, HIV acquisition and the use of PrEP among BIPOC. These social determinants include, among others, economic stability, access to quality education, and access to quality healthcare.

The uptake of PrEP has been shown to be impacted by unmet social determinants of health (SDOH) needs. These include basic needs (e.g., food, shelter, water), health/social service needs (e.g., healthcare), and economic needs (e.g., money for savings). Socioeconomic factors identified to affect PrEP uptake included lack of insurance, difficult access to transportation, and inflexible work situations. Individuals with more unmet SDOH needs may have other priorities that divert their focus from obtaining preventative health services.

There are multiple socioeconomic factors to consider when looking at the barriers to PrEP uptake among disproportionately impacted communities at both the individual-level and structural-level barriers. Individual-level barriers to PrEP uptake include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

What providers can do to improve PrEP utilization among BIPOC people?

- Prior to meeting your patient:

- Check your bias and personal story: what baggage do you bring to the table?

- Look at their chart to get a sense of who they are

- Beware of microaggressions

- Don’t speak in generalities

- Don’t assume race/ethnicity

- Don’t assume gender/sexual identity

- Don’t assume pop culture references

- Condescension while being questioned

- What to bring to the patient interaction?

- Any member of the care team (e.g., PrEP Navigator, Case Manager) can learn about the familial context and/or patient’s culture and share what they learn with the provider and/or providers can build rapport by expressing an interest in learning about these aspects of the patient's life as they get to know each other

- Questions around culture

- Familial Context

- Learn about the familial responsibilities of the patient

- Learn about the patient’s biological/chosen support system

- Ask about personal & familial experience with health insurance

- Ensure prescriptions are affordable within the patient’s budget

- Discuss ease of getting to your clinic

- Discuss ease of physically accessing referral care and/or pharmacies

- Words Matter

- Providers can utilize a mutually agreed-upon opening script within the clinic about how to frame these questions. An example could be: "I'm interested in learning about how we can support you now or in the future" or "it's important to me to know if there are any issues that are coming up even if I can't help right away"

- It is not “dumbing-down” to speak to patients in a culturally-responsive manner

- If you do not speak their vernacular, learn

- If you misspeak & offend, apologize

- Watch for “Why” questions: instead of asking “Why do you want to take PrEP?” or “why don’t you use condoms,” you can ask “Tell me about what makes you want to take PrEP” or “Tell me about how you make decisions about condoms”

- Do not ask: “Do you understand?”

- Ask: “Please tell me what you think I said. It is important that we are on the same page.”

- Support Resilience

- It is important to “reframe the misconception to see [Black LGBTQ people] as “at risk” and instead see them as “at promise” for a future of good health and well-being anchored in their own resilience and supported by our abilities as staff, providers, and institutions to provide services to contribute to their resilience.”

- Consider exploring strengths and coping strategies by asking: What do you love about yourself? What has helped you to keep going even when times are hard? How can I best help you as you start PrEP?

- Care to Treatment

- Take time to address fears about a particular drug, pharmaceutical company, or the healthcare industrial complex. Take care not to argue a point, but rather to hear their perspective/concerns, then ask for permission to share additional information or your experience as a clinician, if appropriate.

- Storytelling of other patients’ experiences with medication is key for trust

- Share personal experience when appropriate, this is critical when recommending preventative care

- Be transparent if you or your clinic have been involved with any clinical trials or are receiving funding from pharmaceutical companies

- Create a safe & welcoming clinic

- Staff Diversity

- Actively engage clinic leadership to champion Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Anti-Racism efforts.

- Hire and retain staff that reflect the patient population, especially clinicians

- Encourage clinic leadership (including Human Resources) to adopt workplace policies, procedures, and compensation rates that foster retention of a culturally concordant workforce.

- Speak with staff and conduct quarterly trainings on cultural responsiveness.

- Have inclusive imagery and signs visible.

- Have BIPOC-centric brochures & magazines in waiting areas

- Post a Diversity & Inclusion statement in a conspicuous location

- Bringing them back to care

- Before the patient leaves the visit:

- Confirm the best form of future contact

- If you have a portal, make sure that it is on their mobile phone

- Ask them to send you a Test Message

- Introduce them to the person(s) who may follow-up

- Patients, clients, customers may come once, but maybe not again

- Look at your client-level data and see if your BIPOC clients are coming back for their appointments

- It’s probably not them … It may just be you (and/or your staff)

- Conduct an anonymous survey of patients

- Be committed to receiving feedback and change

- Reiterate that you are committed to their success

- Ask for a verbal report card before the patient leaves

Address Social Determinants of Health whenever possible. One of the findings in a PrEP navigation study highlights the benefit of offering clinical and non-clinical PrEP services to clients in one place which facilitates clients’ access to PrEP services. A co-located approach can ameliorate barriers such as time constraints, PrEP cost and lack of insurance, and low/limited income. This is particularly important when there is a low PrEP uptake among racial and gender minorities who are disproportionately affected by HIV.

- Hire a PrEP Navigator or train community health workers in PrEP Navigation

- Partner with eligibility workers to optimize insurance coverage

- Support with transportation benefits

- Connect to food and housing resources

- Connect to benefits/social services providers

- Follow up on any issues related to medication or care related costs or delays

Make PrEP easier to talk about:

- Talk about PrEP with everyone.

- Mention PrEP with every HIV test order/result universally.

- Make PrEP easier for patients to get:

- Stock generic PrEP and use it as first line agent (cost-effective).

- Offer tele-prep follow-up as an option.

- Do not withhold next prescriptions due to missed appointment (as long as the HIV test is complete and negative).

Offer options:

- Consider offering a 1-month follow-up if the patient is ambivalent or unsure about adherence (before extending to every 3 month visits).

- Honor choice: Continue to offer all tools in the HIV prevention toolkit even if it’s not the provider’s preference.

- If patient is not ready for sexual history discussion on first visit, that’s ok. Revisit this discussion at next appointment or when rapport is built.

- Greater than AIDS PrEP campaign “Powered by PrEP”: POC centered messaging including testimonials in English and Spanish

- REACH LA’s WAP campaign

- Black AIDS Institute: black cis women

- Cardea: HIV Care for Native patients

- Labeling transwomen as MSM

- MSM of color - Leo Moore presentation

- People of trans experience - evidence of lack of interaction with gender-affirming hormones

- Reproductive health - evidence of safety in conceiving, pregnancy & lactation. (HIVE toolkit)

- Seicus PrEP Education for Youth-Serving Primary Care Providers Toolkit

- Lack of diversity in healthcare Infographic

- National LGBT Health Education Center: “Understanding and Addressing the Social Determinants of Health for Black LGBTQ People”

- Same-day Oral PrEP quick guide: https://www.ebgtz.org/resource/same-day-prep/