PrEP Provider Toolkit

| Site: | Pacific AIDS Education & Training Center |

| Course: | PrEP Provider Toolkit |

| Book: | PrEP Provider Toolkit |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, November 21, 2024, 2:48 AM |

WELCOME

Welcome

Thank you for your interest in the Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center PrEP toolkit for providers.

Welcome to the Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center’s provider toolkit for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). You are about to begin an educational session that will significantly improve the quality of care you provide and help contribute to the global efforts to eradicate the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

Since its discovery in the 1980s, HIV has been a major public health issue that continues to affect millions worldwide. Fortunately, incredible medical advancements have been made in this field that not only significantly improve the lives of those living with HIV, but can also effectively prevent the occurrence of new infections.

PrEP is one of modern medicine’s most powerful tools in disease prevention as it is highly efficacious, well-tolerated, and cost-effective. However, despite its existence for the past decade (since 2012), utilization has been fairly limited due to provider knowledge, comfort, and deliverability barriers.

This site is specifically designed to improve your understanding and confidence in providing this essential tool. You will be guided through the most relevant and practical aspects of PrEP care and be provided with various resources to help you streamline PrEP into your everyday practice.

This toolkit primarily utilizes information from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) PrEP Clinical Guidelines, updated in December 2021. Minor modifications of these guidelines will be suggested to reduce any confusion that may deter providers from utilizing PrEP while allowing for more comprehensive care that doesn’t jeopardize safety.

The information presented here will be directed towards clinicians and, at times, may get a bit technical. But rest assured that if you need further support and guidance, there is a free hotline available to help you address any and all aspects of PrEP care.

National Clinicians Consultation Center

855-HIV-PrEP (855-448-7737) Monday – Friday, 9am – 8pm Eastern Time

Voice mails can be left at any time.

Lastly, PrEP delivery and management are not meant to fall solely onto the shoulders of providers. Like all the other conditions you manage, the prevention of HIV with PrEP is best performed with a team approach, utilizing everyone in your practice setting from the front desk to the back office. However, if you decide that PrEP is not something you want to provide, patients can be directed to resources to learn more about PrEP and find a PrEP provider.

← Browse the tabs to learn more.

Use the navigation in the lower right corner ↘ to begin the training.

What is the Pacific AETC?

The

Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center (Pacific AETC) is a member of a national

AIDS Education and Training Center network of eight regional and three national

centers, covering all 50 states, as well as US Territories and Jurisdictions.

Funding is provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

HIV/AIDS Bureau through the Ryan White Program, Part F.

The

Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center (Pacific AETC) is a member of a national

AIDS Education and Training Center network of eight regional and three national

centers, covering all 50 states, as well as US Territories and Jurisdictions.

Funding is provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

HIV/AIDS Bureau through the Ryan White Program, Part F.

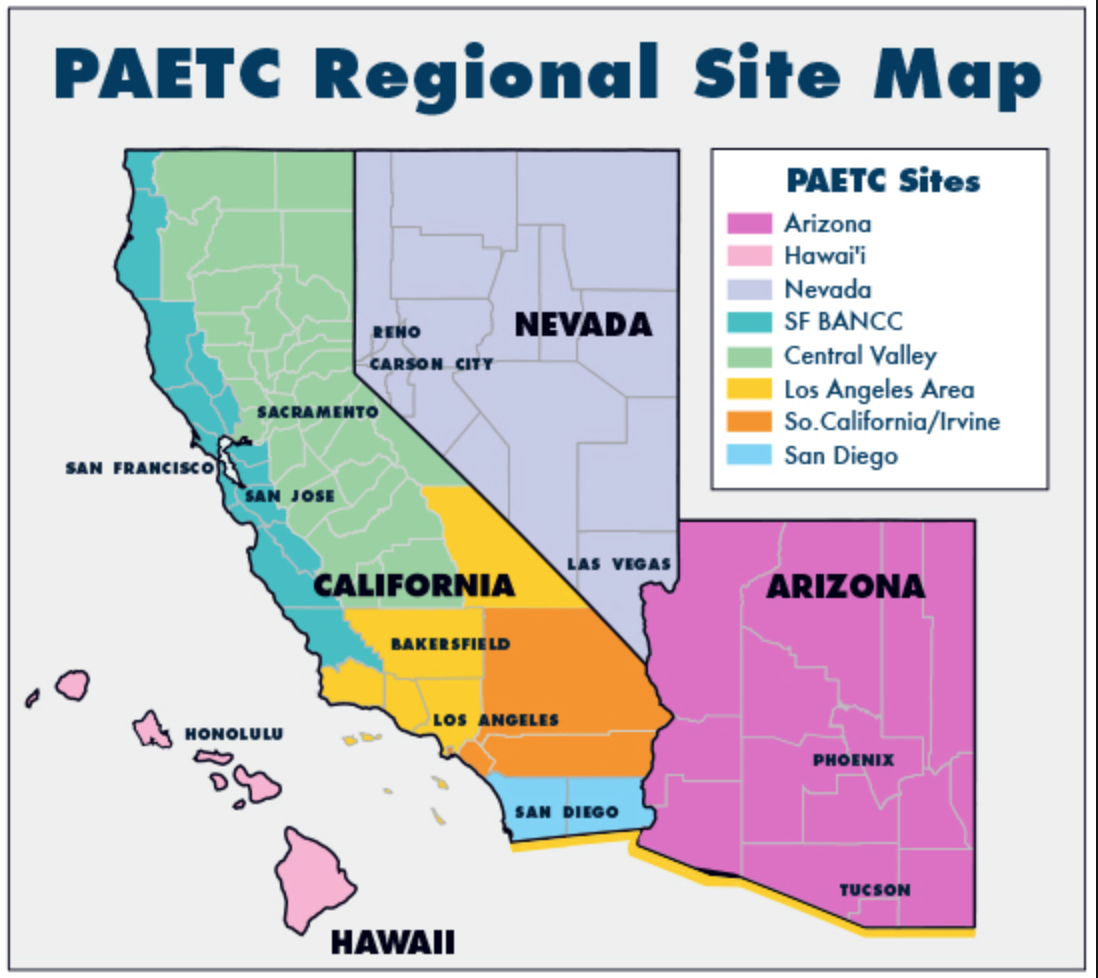

Pacific AETC works to expand the number and ability of healthcare professionals and organizations in the Pacific region to provide high-quality HIV-related services to increase access to healthcare and decrease health inequities. We work with health care providers, clinics, health jurisdictions, and policymakers in Arizona, California, Hawai`i, Nevada, and the US Affiliated Pacific Island Jurisdictions.

A network of eight Local Partners (LPs) provides services on local and regional levels. Five LPs are located throughout California, with state-wide programs in Arizona, Nevada, and Hawai’i. The Hawai’i LP also covers the six U.S. Pacific Jurisdictions (Guam, American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, North Mariana Islands, and Palau).

Each LP has its roster of qualified faculty, programs, and activities designed to meet their local region’s or state’s needs. LPs are based at academic medical centers, with access to highly qualified HIV specialists and community expertise. Contact your local AETC for details about training and capacity-building opportunities. Continuing education credit is available for many activities.

Target Audience

![]() Pacific AETC offers

education, training, and capacity-building programs specifically designed to

improve HIV/AIDS care, treatment, and prevention services for ALL interdisciplinary

team members. This includes but is not limited to:

Pacific AETC offers

education, training, and capacity-building programs specifically designed to

improve HIV/AIDS care, treatment, and prevention services for ALL interdisciplinary

team members. This includes but is not limited to:

- Mental Health Providers

- Social Workers

- Case Managers

- Physicians

- Nurses

- Advance Practice Nurses

- Physician Assistants

- Dentists

- Pharmacists

- Community Health Workers

Local Partners & State Office of AIDS

A network of eight Local Partners (LPs) provides services on local and regional levels. Five LPs are located throughout California, with one each in Arizona, Nevada, and Hawai’i. The Hawai’i LP also covers the six U.S. Pacific Jurisdictions (Guam, American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, North Mariana Islands, and Palau).

Each LP has its roster of qualified faculty, programs, and activities designed to meet their local region’s or state’s needs. LPs are based at academic medical centers, with access to highly qualified HIV specialists. Contact your regional AETC for details about training and capacity building opportunities. Continuing education credit is available for many activities.

Basics of HIV

Understanding the disease in which we

are trying to prevent is important to truly value the power and potential of PrEP. In this section, we will be covering how HIV is transmitted, how we test for HIV, how new HIV infections present, and important public health statistics about HIV.

Laying down this foundational understanding will help make sense of the information provided in the following sections.

Understanding the disease in which we

are trying to prevent is important to truly value the power and potential of PrEP. In this section, we will be covering how HIV is transmitted, how we test for HIV, how new HIV infections present, and important public health statistics about HIV.

Laying down this foundational understanding will help make sense of the information provided in the following sections.

Transmission risk factors

To truly understand and appreciate the potential of PrEP, it is worthwhile to briefly review the disease it prevents. HIV is a retroviral infection that specifically attacks the CD4 cells in the immune system.

Transmission of HIV typically occurs through contact with blood or fluids from the rectum, penis, or vagina. Additionally, HIV can be transmitted from a mother to her child perinatally or through breastfeeding. Exposure of HIV to damaged mucosal tissue or directly into the bloodstream is required for transmission. Exposure to HIV on intact skin does not pose a risk, nor do acts such as hugging, kissing, or sharing utensils.

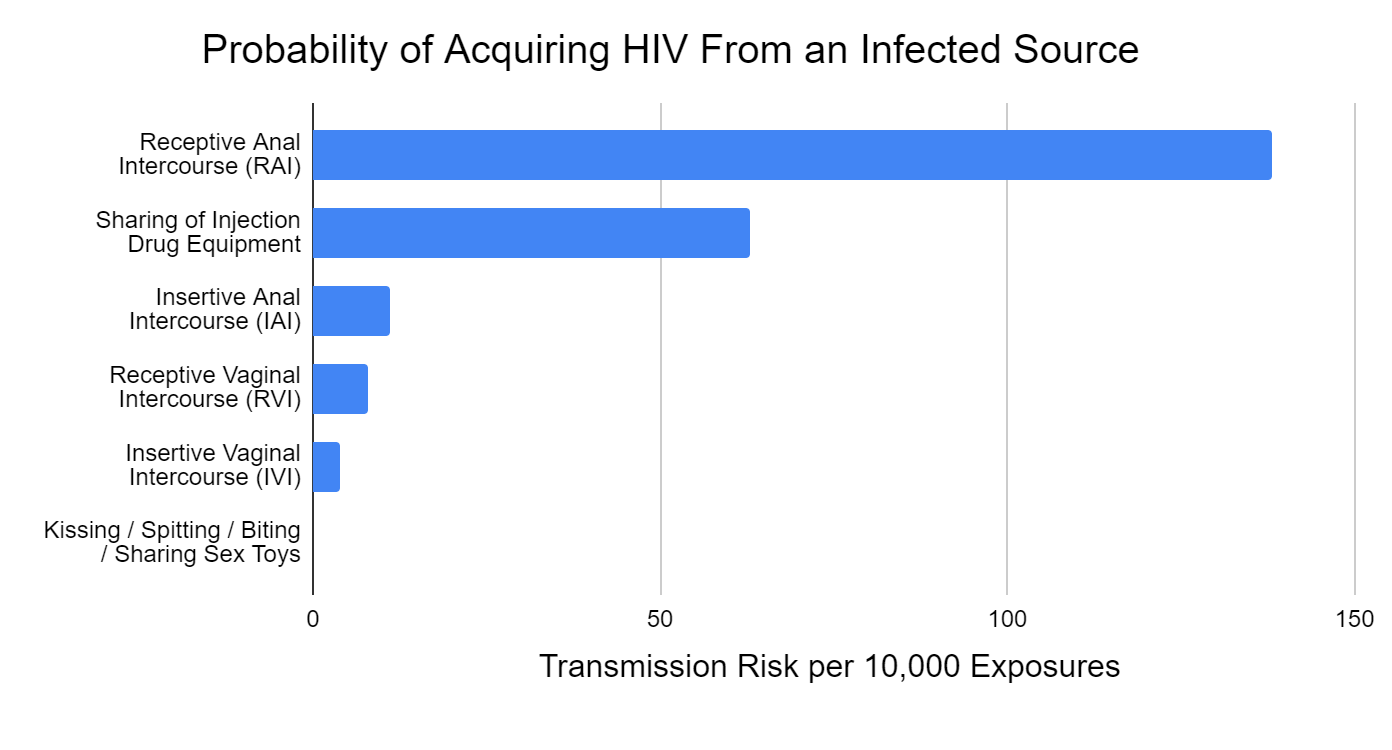

Figure 1 depicts the estimated likelihood of acquiring HIV from an infected source based on the type of exposure. Note that the second highest risk factor occurs among people who inject drugs (PWIDs), which is a population of rising concern. For further information about HIV transmission: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/transmission.html

Click for image for full size view

Click the title of the figure to view source.

Figure 1. - Estimated Probability of Acquiring HIV from an Infected Source by Exposure Type

Source: Patel, Borkowf, C. B., Brooks, J. T., Lasry, A., Lansky, A., & Mermin, J. (2014). Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review. AIDS (London), 28(10), 1509–1519. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000298

Pretty, Anderson, G. S., & Sweet, D. J. (1999). Human bites and the risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 20(3), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000433-199909000-00003

Factors contributing to HIV transmission are fundamentally important to understand as it helps discern which patients are at the highest risk and how to protect them best.

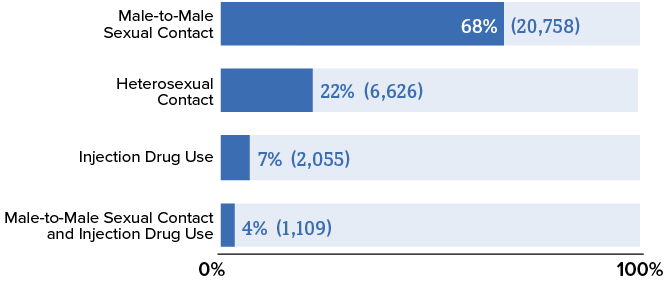

Anal sex or sex under the influence of drugs and alcohol has a higher likelihood of damaging the protective mucosal layer, which facilitates HIV transmission. Local inflammation caused by sexually transmitted infections (STI) also decreases the integrity of the mucosal lining. This partly explains why groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM) have higher rates of HIV transmission (Figure 2).

The CDC has a helpful tool that estimates the risk of sexually transmitted HIV based on various factors. It provides a powerful graphic that can be used with patients during visits to improve their self-perceived risk: https://hivrisk.cdc.gov/risk-estimator-tool/#-mb|iai

Figure 2. - New HIV Diagnoses in the US by Transmission Category, 2020

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2020. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2020-updated-vol-33.pdf

HIV Testing

The recommended tests for HIV can vary based on the clinical scenario and the type of PrEP medication being utilized. Let’s briefly review this to build a foundational understanding of HIV testing options, their indications, and their limitations.

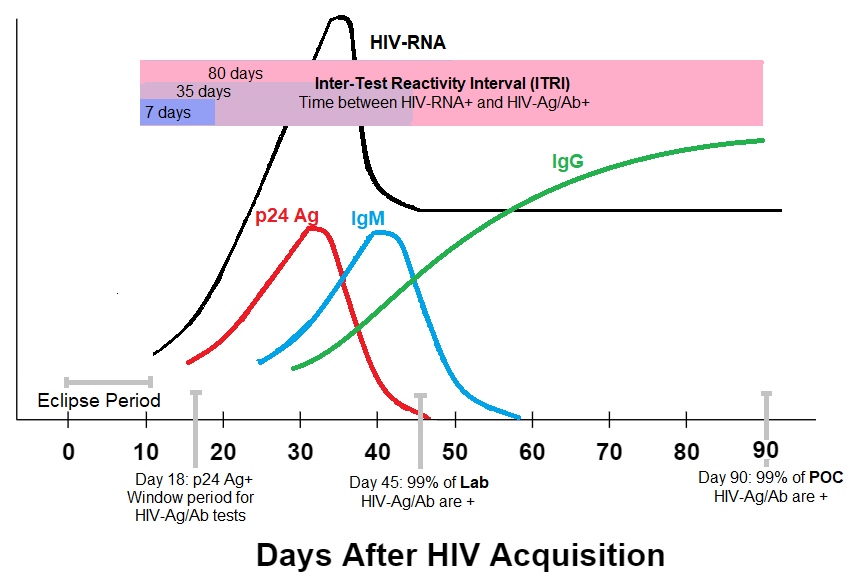

HIV-RNA

- Sometimes called nucleic acid test (NAT) or “viral load”

- Measures the amount of circulating HIV genetic material

- Becomes detectable ~10 days after HIV acquisition

p24 antigen (Ag)

- A structural protein found in the HIV capsid

- The antigen component of combined HIV-Ag/Ab testing.

- Becomes detectable ~18 days after HIV acquisition

HIV antibody (Ab)

- Antibodies against HIV; starts with IgM which gets replaced over time with IgG

- The antibody component of combined HIV-Ag/Ab testing

- Becomes detectable ~24 days after HIV acquisition

Click image for full size view

Click the title of the figure to view source.

Figure 3. - Timing of HIV Test Positivity After Acquisition

Fiebig, Wright, D. J., Rawal, B. D., Garrett, P. E., Schumacher, R. T., Peddada, L., Heldebrant, C., Smith, R., Conrad, A., Kleinman, S. H., & Busch, M. P. (2003). Dynamics of HIV viremia and antibody seroconversion in plasma donors: implications for diagnosis and staging of primary HIV infection. AIDS (London), 17(13), 1871–1879.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200309050-00005

Branson, B.M., Owen, M.S., Wesolowshi, L.G., Bennett, B., Werner, B.G., Wroblewski, K.E., Pentella, M.A. (2014). Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: updated recommendations.

https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc.23447

Delaney, Hanson, D. L., Masciotra, S., Ethridge, S. F., Wesolowski, L., & Owen, S. M. (2017). Time until emergence of HIV test reactivity following infection with HIV-1: implications for interpreting test results and retesting after exposure. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 64(1), 53–59.

https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw666

Newly acquired HIV infections take some time to make substantial copies of its genome. During this eclipse period, which typically lasts 10-12 days, we are unable to detect an HIV infection with any type of test. This eclipse period also happens to be the window period for HIV-RNA tests.

The window period is the time between HIV acquisition and lab test positivity.

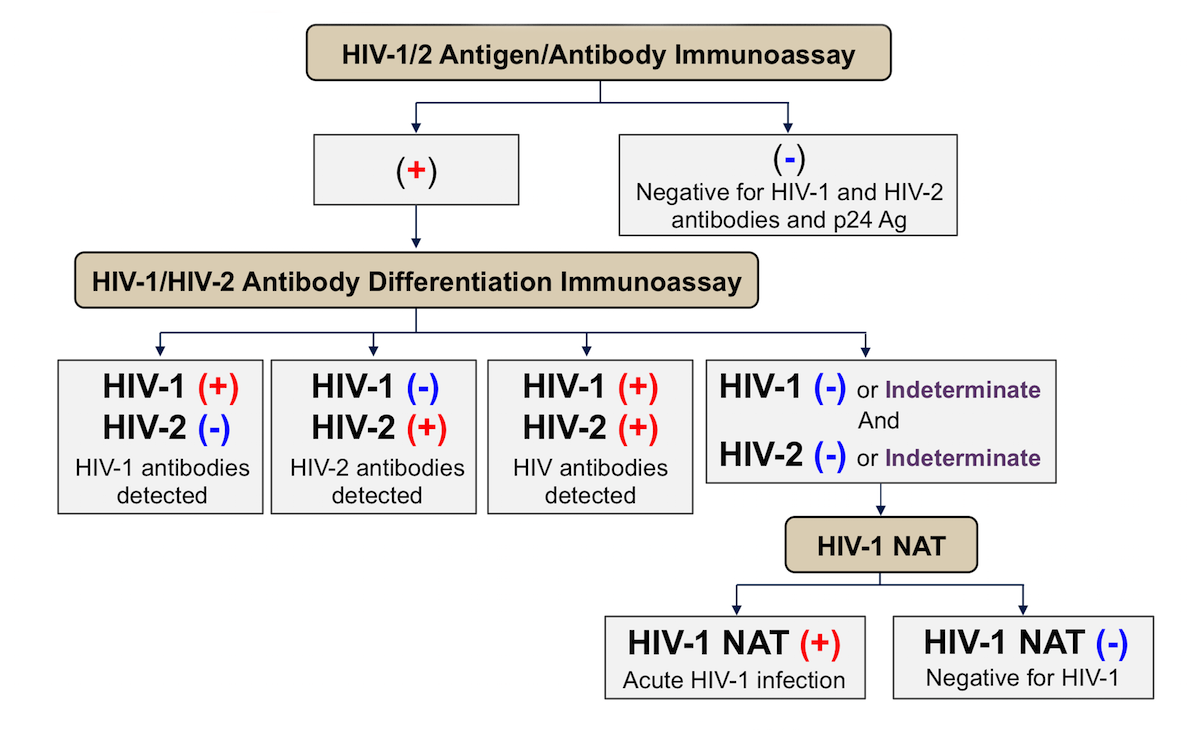

Each successive generation of HIV-Ag/Ab testing has worked to shorten the window period to allow for earlier diagnosis. The currently recommended and most commonly used HIV-Ag/Ab 4th-generation test checks for the p24 Ag, HIV-IgM, and HIV-IgG. The testing algorithm is presented in Figure 4. This test can be performed in the laboratory or as a point-of-care (POC). The only POC HIV-Ag/Ab test recommended in the context of PrEP is the Abbott Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo, a fingerstick test that generates results in 20 minutes. (1)

DetermineTM HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2022, from

https://www.globalpointofcare.abbott/en/product-details/determine-1-2-ag-ab-combo.html

Figure 4 - HIV-Ag/Ab testing algorithm

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Quick reference guide: recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines_testing_recommendedlabtestingalgorithm.pdf

The window period for a laboratory based 4th-generation HIV-Ag/Ab test is between 18-45 days; the point-of-care (POC) version has a slightly longer window period of 18-90 days. After the window period, these tests will detect 99% of all newly acquired HIV infections.

Although HIV-RNA tests have the shortest window period, we do not routinely rely on this test for screening as it is costly and places a high burden on laboratories.

HIV-RNA is typically only used in the following scenarios:

- Monitoring disease activity in someone with a known HIV infection

- Checking for HIV acquisition during the inter-test reactivity interval

The inter-test reactivity interval (ITRI) is the time between HIV-RNA test positivity and HIV-Ag/Ab test positivity.

As highlighted in purple boxes in Figure 3, this ITRI can be as short as a week to as long as 80 days. Thankfully, it has been determined that the ITRI of current Ag/Ab tests to capture 95% of new infections is just one week. (2) In other words, the current HIV-Ag/Ab tests that we use can reliably detect new infections just a week after HIV-RNA tests can.

Delaney, Hanson, D. L., Masciotra, S., Ethridge, S. F., Wesolowski, L., & Owen, S. M. (2017). Time until emergence of HIV test reactivity following infection with HIV-1: implications for interpreting test results and retesting after exposure. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 64(1), 53–59.

https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw666

However, this indicates that clinical scenarios still exist where HIV-RNA testing is needed before starting PrEP. We will be covering this in detail in the coming sections. Admittedly, this is the most challenging portion of PrEP care though it does not need to be applied in the vast majority of cases, so do not be deterred.

The recommended tests for HIV can vary based on the clinical scenario and the type of PrEP medication being utilized. Let’s briefly review this to build a foundational understanding of HIV testing options, their indications, and their limitations.

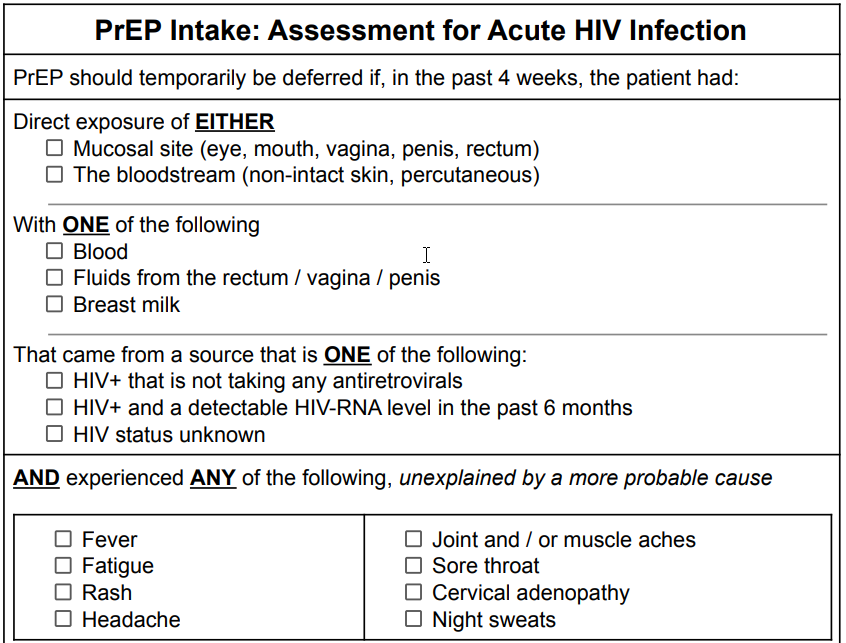

Acute HIV infections

The early stages of an HIV infection present many challenges in clinical decision making. In the previous section, we covered how objective measures can vary based on the timing of infection. Using subjective measures in the clinical setting is even more challenging, if not impossible, to accurately diagnose acute retroviral syndrome (ARS).

Only half of new HIV infections are estimated to cause symptoms between 2-4 weeks after acquisition. Among those who reported symptoms, only fever and fatigue occurred in most cases. Other less commonly reported symptoms include myalgia, rash, headache, sore throat, cervical adenopathy, joint aches, night sweats, and diarrhea. (3) This leads to a very broad differential diagnosis. Taken altogether, symptoms of ARS are both unreliable and extremely nonspecific; and thus, should not be used in isolation to make clinical decisions.

Daar, Pilcher, C. D., & Hecht, F. M. (2008). Clinical presentation and diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Current Opinion in HIV & AIDS, 3(1), 10–15.

https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0b013e3282f2e295

Furthermore, after this short period of time when symptoms occur, patients can go on for years without any new complaints. In fact, despite collective efforts to perform more routine testing, it is estimated that about 13% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) are unaware of their diagnosis and account for over a third of new infections. (4)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-26-1.pdf

How, then, can we improve our clinical gestalt for a condition that presents so ambiguously and has such an enormous impact on the lives of individuals and communities?

The answer to this question is complex, but it relies on several key points.

- An environment and approach that fosters patient comfort and trust is necessary to start relevant conversations

- Thorough and accurate sexual and substance use histories must be obtained

- A firm understanding of HIV tests must be developed and they should be utilized judiciously.

We will cover techniques and frameworks to help you improve these skills in the coming sections.

Important HIV Epidemiology

Prevalence captures the proportion of a population that currently lives with a condition. Incidence captures the proportion of a population that is newly infected with a condition.

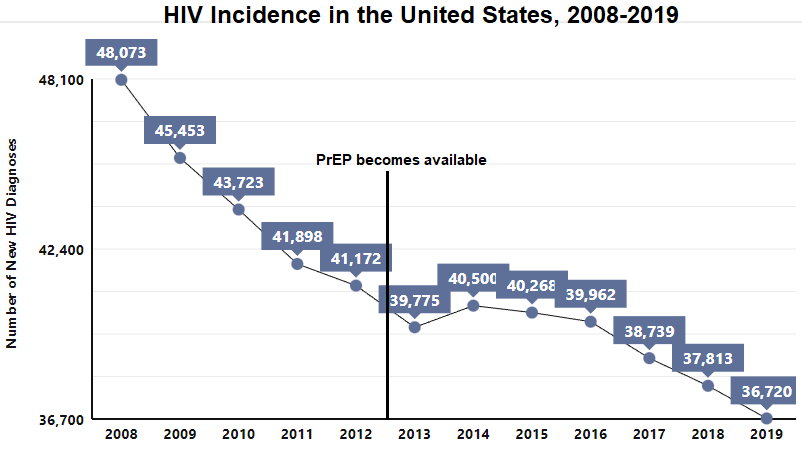

Medical advancements such as antiretroviral therapy (ART) contribute to longer life expectancies among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and, thus, rising prevalence rates. When it comes to PrEP, we are more concerned with incidence rates as it is a preventive tool to avoid new infections from occurring.

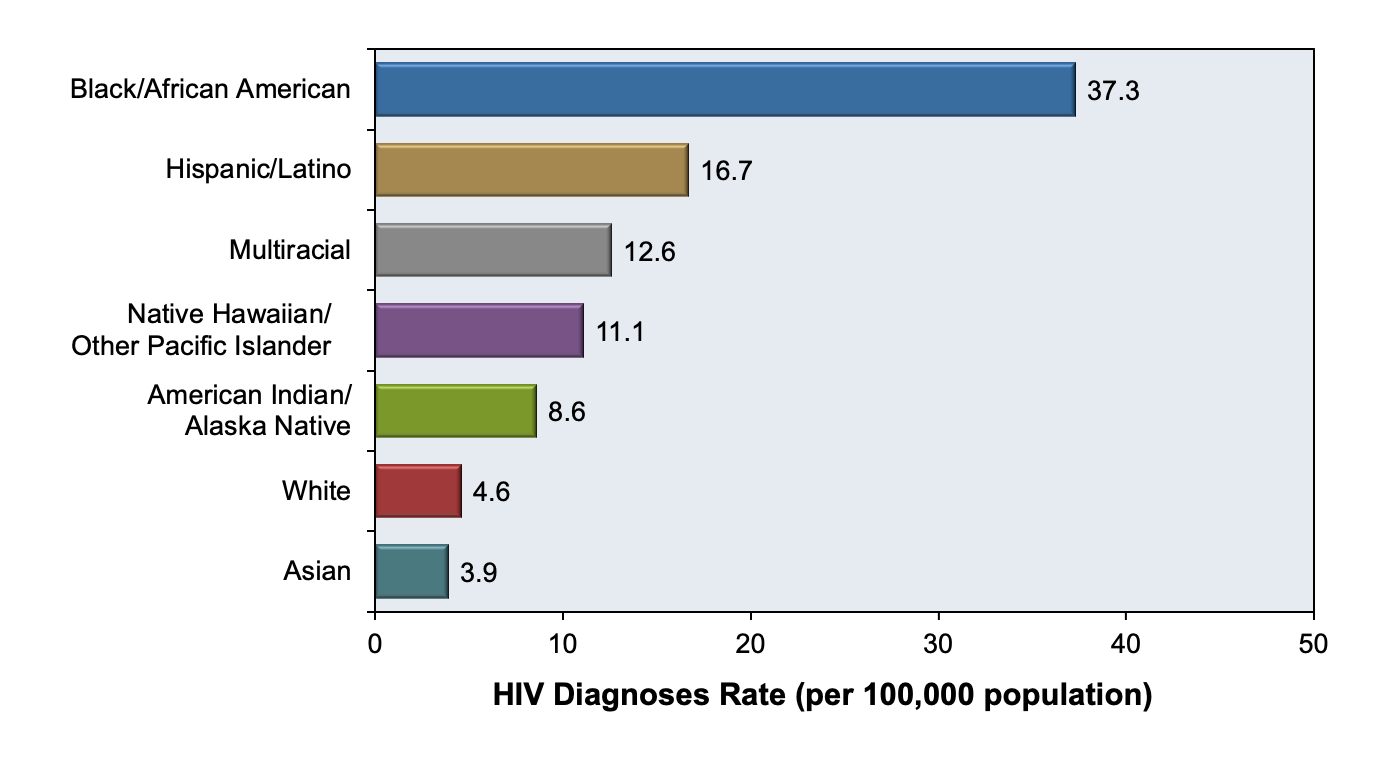

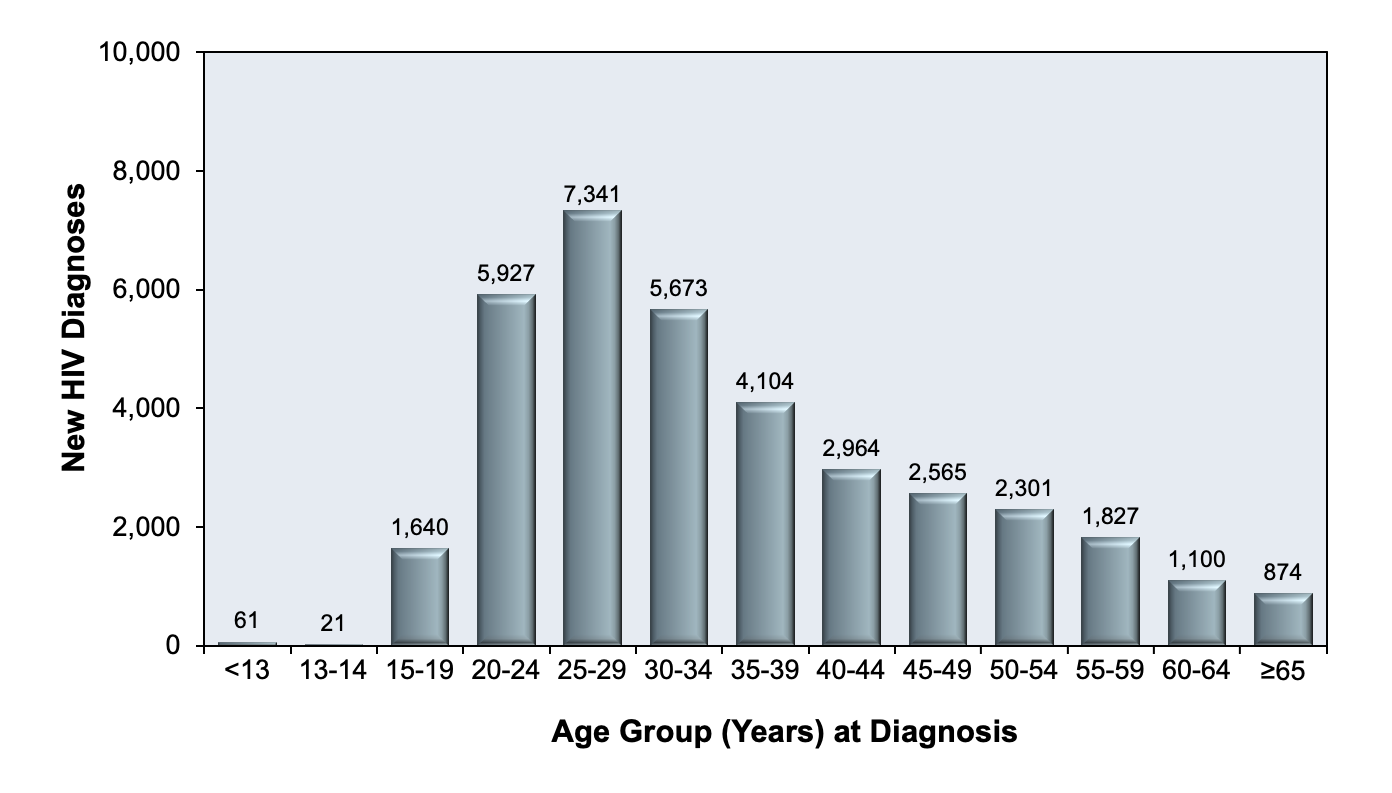

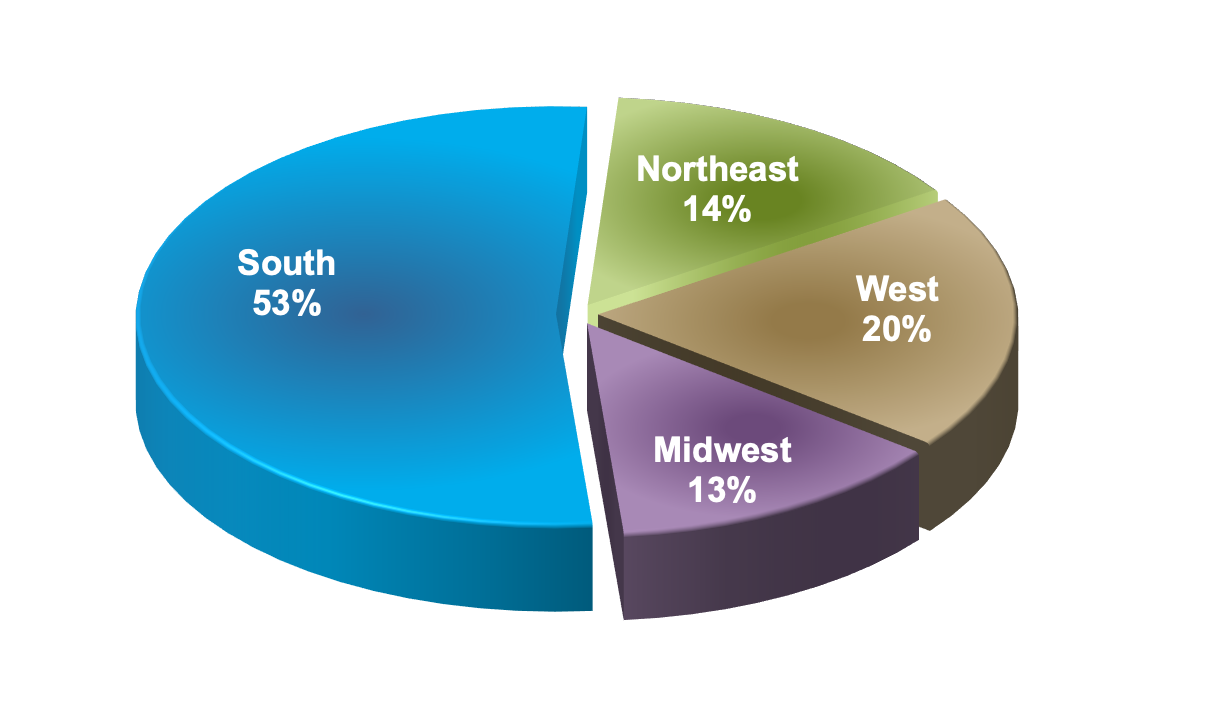

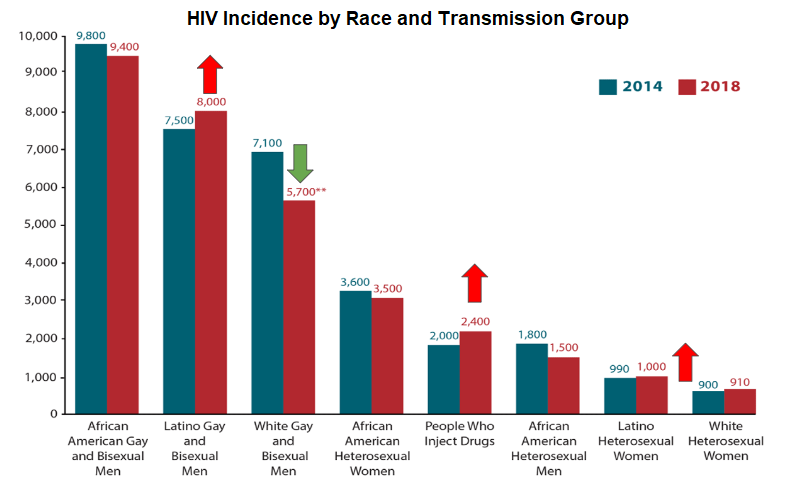

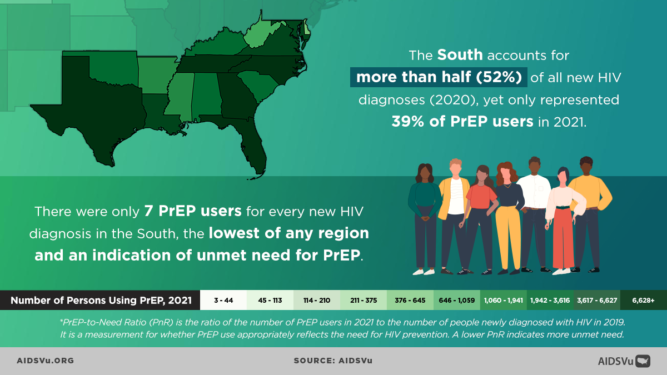

Figure 5 shows that the incidence of HIV in the United States has been steadily declining over the years. Despite this seemingly reassuring trend, when viewed with a closer lens, concerning disparities are revealed across racial groups, age groups, and geographic regions. HIV disproportionately affects Black/African Americans between the ages of 20-34, and a startling majority of all new HIV cases occur in Southern states alone (Figures 6-8). (5)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf

It is also worth pointing out that the major reductions in HIV incidence occurred before PrEP was introduced. Improved testing and treatment of those living with HIV account for these early changes in incidence rates. This highlights the rather limited impact PrEP has had on this crucial statistic.

Since its availability, PrEP has predominantly benefited white gay and bisexual men. HIV incidence is worsening among groups of growing concern, such as Latino men and women and people who inject drugs (PWIDs) (Figure 9).

Most of the graphics shown below have been adopted from the National HIV Curriculum, a free resource created by the University of Washington and funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). It includes easy to follow, self-guided modules that provide an in-depth understanding of HIV: https://www.hiv.uw.edu/

They also make resources to improve your understanding of STIs, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C. Both CME and CNE credits can be earned by completing these self-study modules.

Click image for full size view

Click the title of the figure to view source.

Figure 5 - Incidence Rates in the United States, 2008-2019

Figure 6 - Incidence Rates in the United States in 2019, by Race/Ethnicit

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf

Graph obtained for the HIV National Curriculum at www.hiv.uw.edu. Accessed September 1, 2022.

Figure 7 - HIV Incidence in the United States in 2019, by Age Group

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf

Graph obtained for the HIV National Curriculum at www.hiv.uw.edu. Accessed September 1, 2022

Figure 8 - New HIV Diagnosis in the United States in 2019, by Region of Residence

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf

Graph obtained for the HIV National Curriculum at www.hiv.uw.edu. Accessed September 1, 2022.

Figure 9 - New HIV Diagnosis in the United States in by Race and Transmission Group, 2014-2018

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2019. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf

Patient-centered approach

Discussing PrEP naturally requires very sensitive information to be shared. A mindful and patient-centered approach is necessary to instill the comfort and build proper rapport. In this section, we will review gender-related terminology and how to effectively obtain a sexual and substance use history. Tailoring your approach will continuously involve trial and error but over time, you will find what works best for you and your patients.

Discussing PrEP naturally requires very sensitive information to be shared. A mindful and patient-centered approach is necessary to instill the comfort and build proper rapport. In this section, we will review gender-related terminology and how to effectively obtain a sexual and substance use history. Tailoring your approach will continuously involve trial and error but over time, you will find what works best for you and your patients.

Review of gender-related terminology

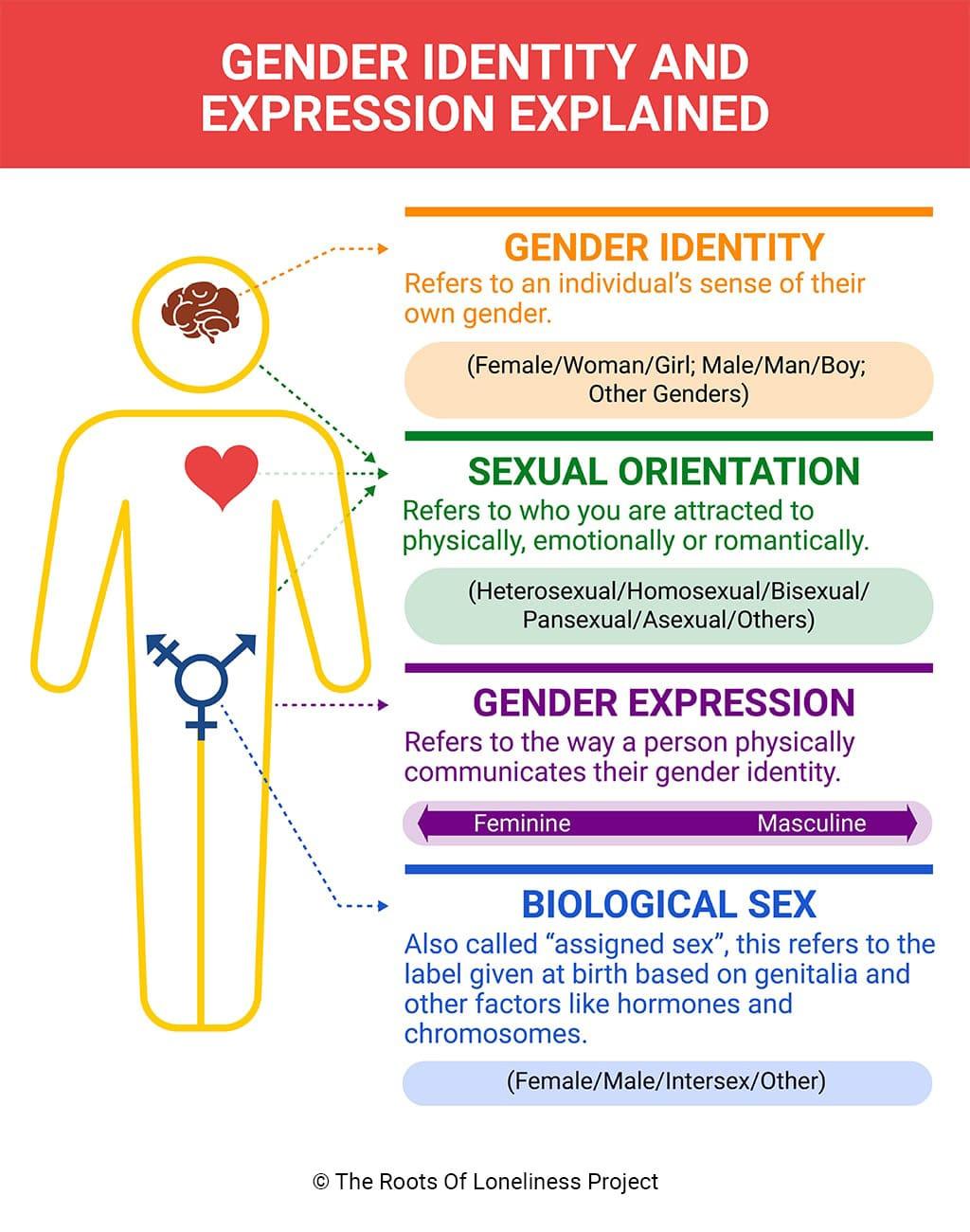

Currently, there are different indications of which PrEP medication to use depending on the sex of the patient. Sex is not the same as gender, nor is it equivalent to, or indicative of, someone’s current anatomy, sexual orientation, or sexual practices. It is easy to confuse these terms which can affect internal biases, patient rapport, and overall quality of care. Therefore, it is worthwhile at this point to review gender-related terminology.

The term sex is used to refer to the designation that is given at birth based on biological factors such as sex chromosomes and genitalia present at birth. Typically, a person is assigned male at birth (AMAB) or female at birth (AFAB). A person may also be assigned intersex when there are conditions that make this determination ambiguous (e.g., congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen insensitivity syndrome, etc.).

There exist social constructs that are tied to a person’s sex which are sometimes called gender norms. These norms encompass things such as roles and expressions. For example, men have to be in positions of power or only women can wear makeup and dresses. An individual may not always identify or agree with these norms or their bimodality.

Gender identity refers to an individual's internal perception of where in the spectrum of gender norms they fit in most. Relatedly, gender expression is the external presentation of this concept - how a person chooses to look.

Someone whose gender identity is congruent with their sex is termed cisgender.

Someone whose gender identity is different from their sex is termed transgender.

A person whose sex is assigned male at birth (AMAB) but identifies as a female is termed a transgender woman (TGW), sometimes referred to as male-to-female (MtF).

Conversely, there are also female-to-male (FtM) transgender persons.

Sometimes, a person may choose to undergo medical therapies and interventions to affirm their gender identity. This may be referred to as transsexual - a subset of the transgender umbrella term. It is never appropriate to assume a patient’s existing anatomy based on their sex or gender.

Click image for full size view

Click the title of the figure to view source.

Figure 10 - Gender Identity and Expressions

Source: Gender identity and how understanding it can ease loneliness. (n.d.). The Roots of Loneliness Project. https://www.rootsofloneliness.com/gender-identity-loneliness

Sexual orientation refers to the physical, romantic, and/or emotional attraction one feels towards another gender(s).

Heterosexuality is the attraction between those of the opposite sex (i.e. straight)

Homosexuality is the attraction between those of the same sex (i.e. lesbian, gay)

A term often used in medicine is men who have sex with men (MSM).

Bisexuality refers to the attraction to those of both sexes. Asexuality is the lack of attraction to both sexes.

Lastly, sexual practices specifically discuss the sexual acts a person engages in.

Some examples include receptive anal intercourse (RAI), insertive anal intercourse (IAI), receptive vaginal intercourse (RVI), insertive vaginal intercourse (IVI), oral sex, masturbation, etc. Similarly, it is never safe to assume the sexual practices of a patient based on sex, gender, or orientation. We will soon discuss how to take a proper sexual (and substance use) history.

For the purposes of PrEP, an important patient population has been defined based on sex and sexual orientation: men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men (MSM/TGWSM). This will be utilized throughout the toolkit, so please dedicate the time needed to understand these definitions.

This is by no means a comprehensive overview of this topic. This section aims to lay a foundation for understanding some of the nuances of PrEP care that will soon be addressed. For a more comprehensive overview of gender-related terminology and definitions: https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/terminology.

Sexual and substance use history

The CDC created a helpful framework for taking a sexual history termed “The 5 P’s”. (6) The National Coalition for Sexual Health expanded this to “The 6 P’s” which includes a “Plus” category that encompasses topics such as pleasure, problems, and pride. (7). This coalition also created a helpful video series to improve your approach when taking a sexual history. (8)

National Coalition for Sexual Health. (2022). A new approach to sexual history taking: a video series. Altarum Institute.

https://nationalcoalitionforsexualhealth.org/tools/for-healthcare-providers/video-series

National Coalition for Sexual Health. (2022). Sexual health and your patients: a provider’s guide. Altarum Institute

https://nationalcoalitionforsexualhealth.org/tools/for-healthcare-providers/asset/Provider-Guide_May-2022.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). A guide to taking a sexual history. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/SexualHistory.pdf

The 6 P’s of a Sexual History

- Partners

- Practices

- Past History of STIs

- Protection

- Pregnancy

- Plus: Pleasure, Problems, & Pride

Given the rising incidence rate of HIV among people who inject drugs (PWIDs), it is important to expand on the second “P” in this framework: Practices.

Although this approach raises the question of drug and alcohol use in the context of sex, a simple follow-up question to further assess these habits could be…

“Have you ever used injection drugs that were not prescribed by a doctor such as heroin, cocaine, meth, or others?”

If the patient answers “yes,” ask further about the frequency of use and most recent use. Most importantly, ask if they ever share drug injecting equipment of any sort. This includes needles, syringes, cookers, filters, etc. A common misconception is that the patient is not at risk for acquiring transmissible infections as long as different injection needles are used. Ask carefully and provide risk reduction strategies when applicable.

Relatedly, bloodborne infections such as HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C can also be transmitted through needles used for tattoos, particularly in correctional facilities. (42) Inquire about any tattoos the patient has or plans on getting to tailor your care and patient education.

Westergaard, R. P., Spaulding, A. C., & Flanigan, T. P. (2013). HIV among persons incarcerated in the USA: a review of evolving concepts in testing, treatment, and linkage to community care. Current opinion in infectious diseases, 26(1), 10–16.

https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835c1dd0

It may not always be feasible to ask every question mentioned in this section; the point of this framework is to help you progressively improve your history-taking skills. Remember that it may take several conversations about PrEP before a patient decides that it is right for them. Even if typical risk factors are not made apparent, it is always worthwhile to at least ask your patients if they have heard of PrEP. A patient will never take something into consideration if they don’t have an awareness of it at all.

Uplifting BIPOC for PrEP Uptake

- Providing PrEP to BIPOC

- Barriers to PrEP Faced by

Communities Disproportionately Impacted by HIV - Why Are We Doing So Poorly?

- What providers can do to

improvePrEP utilization

among BIPOC people?

Providing PrEP to BIPOC

The BIPOC acronym stands for Black, Indigenous and People of Color. The term BIPOC is used to highlight the unique relationship to whiteness that Indigenous and Black people have that shapes the experiences of and relationship to white supremacy for all people of color within a U.S. context. Using the term BIPOC is people-first and allows us to shift away from terms like “marginalized” and “minority.”

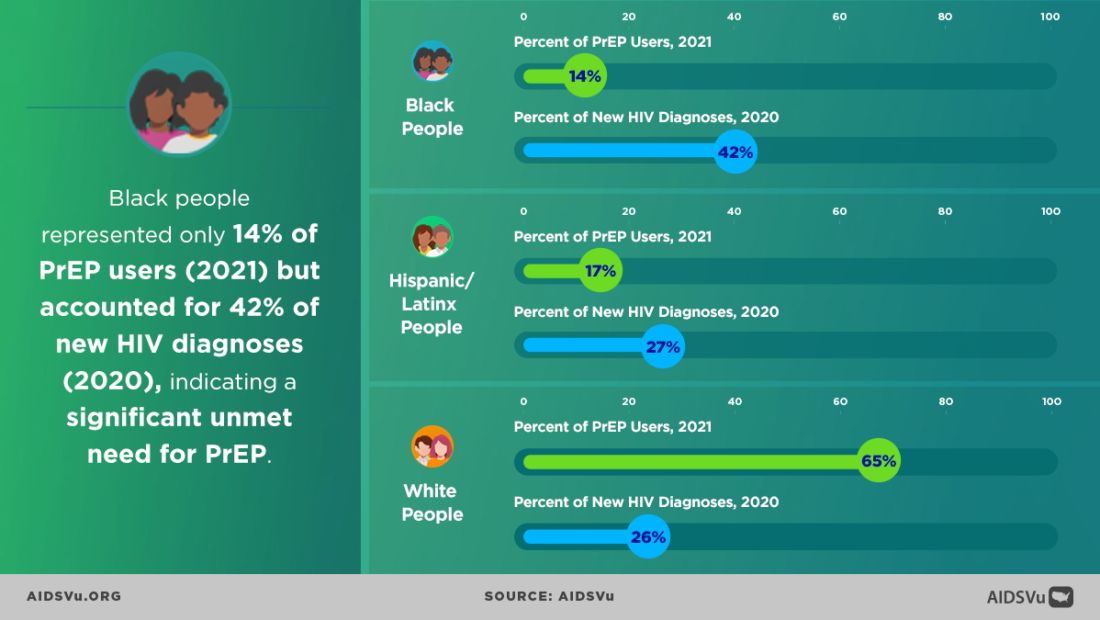

Structural and political determinants of health drive inequities, HIV infection and the use of PrEP among BIPOC. In 2018, at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) new data about PrEP use showed that PrEP medication is not reaching most Americans who could benefit, especially people of color. Out of 500,000 African Americans and nearly 300,000 Latinos across the nation that could benefit from PrEP only 7,000 prescriptions were filled by these communities. This data shows a stark unmet need for HIV prevention medication.

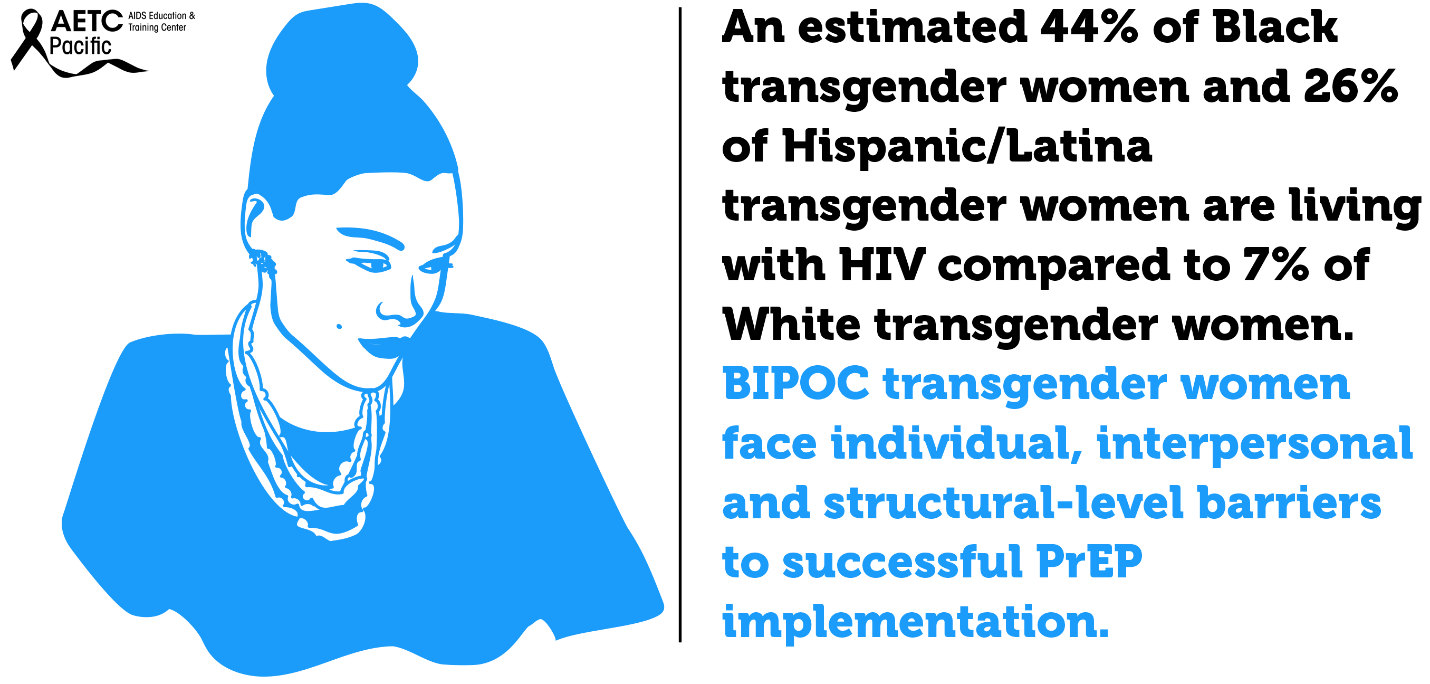

Longstanding social and economic inequities elevate health risks and vulnerabilities for BIPOC, and HIV continues to disproportionately impact these communities, specifically sexual minority men and transgender women in the United States. Disparities are most prominent for Black and Hispanic/Latino groups. At the current rate of infection, estimates suggest that 1 in 2 Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and 1 in 5 Hispanic/Latino MSM will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime; these racial and ethnic disparities in HIV prevalence also extend to Black and Hispanic/Latina transgender women. These communities carry a higher burden of HIV compared to white transgender women. In the U.S., an estimated 44% of Black and 26% of Latino/Hispanic transgender women are living with HIV compared to 7% of white transgender women. The substantial disparity of HIV in these communities is driven by experiences of discrimination and stigma, lack of access to healthcare services, lack of education and employment opportunities, and unstable housing.

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) inequities in the US – both in terms of race and geographical location – have not only persisted in the last decade, but have increased, according to research presented to the 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022) by Dr Patrick Sullivan from Emory University.

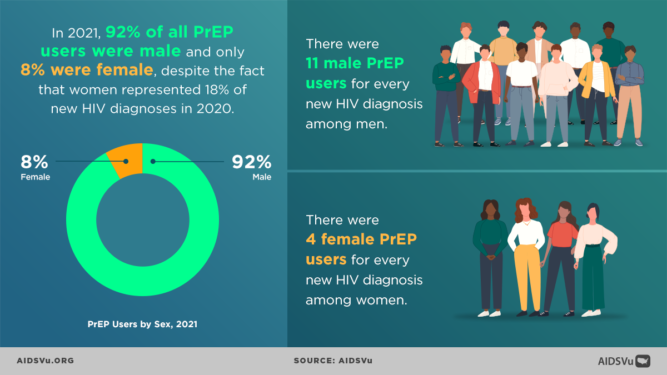

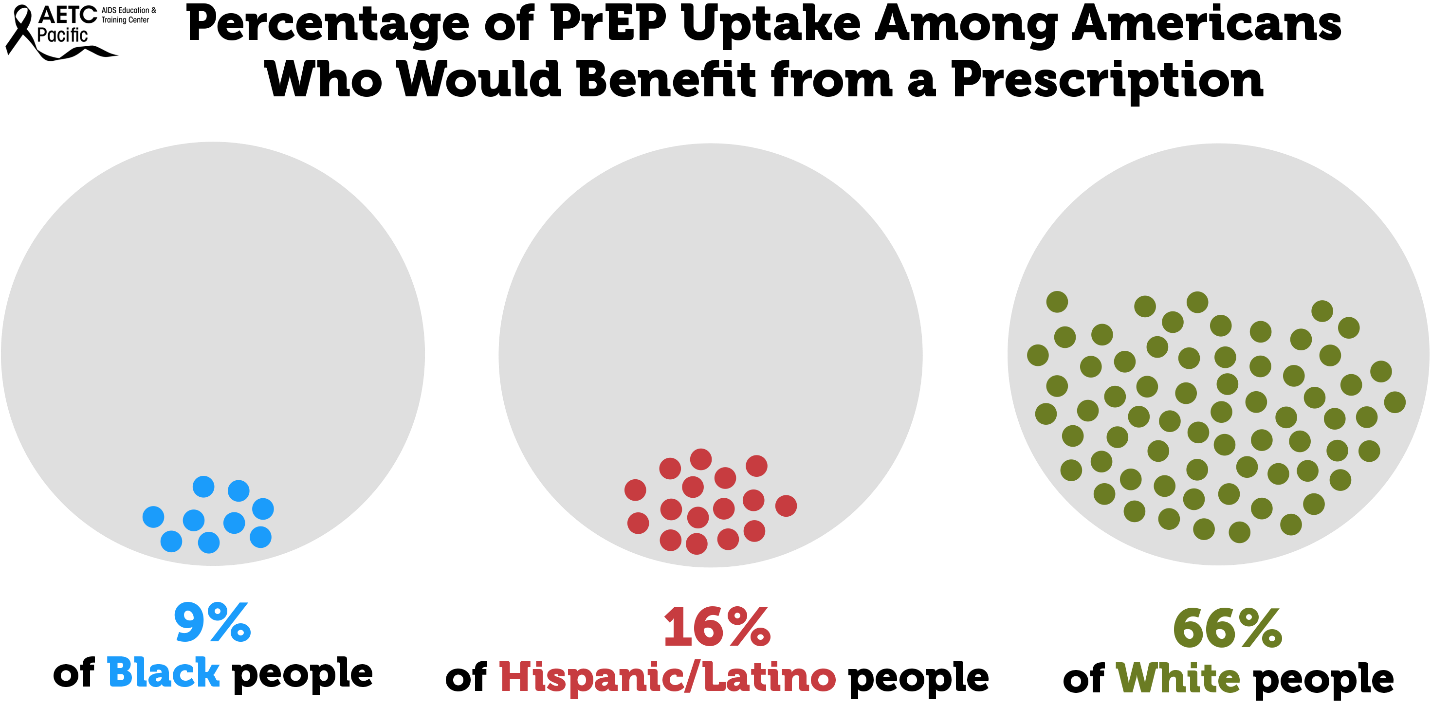

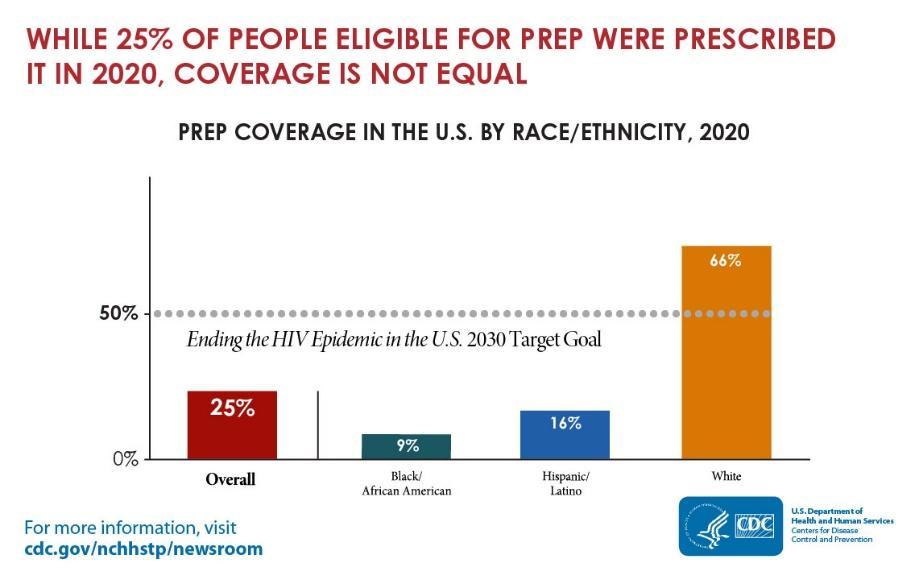

While HIV prevention methods, such as PrEP, are highly effective and necessary in ending the HIV epidemic, serious racial/ethnic disparities, structural inequities, and systemic racism block progress for Black and Hispanic/Latino cis-gender sexual minority men and transgender women in accessing this effective HIV prevention medication. In 2018, at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), new data about PrEP use showed that PrEP medication is not reaching most Americans who could benefit, especially people of color. PrEP uptake has been persistently low among US women, particularly Black cisgender women, who account for 61% of new HIV diagnoses among cis women. Preliminary 2020 CDC data show only 9% (42,372) of the nearly 469,000 Black people who could benefit from PrEP received a prescription in 2020, and only 16% (48,838) of the nearly 313,000 Hispanic/Latino people who could benefit from PrEP received a prescription. Meanwhile, 66% of their White counterparts are utilizing PrEP. This emphasizes the continued unmet need for HIV prevention medication, especially among BIPOC.

Barriers to PrEP Faced by Communities Disproportionately Impacted by HIV

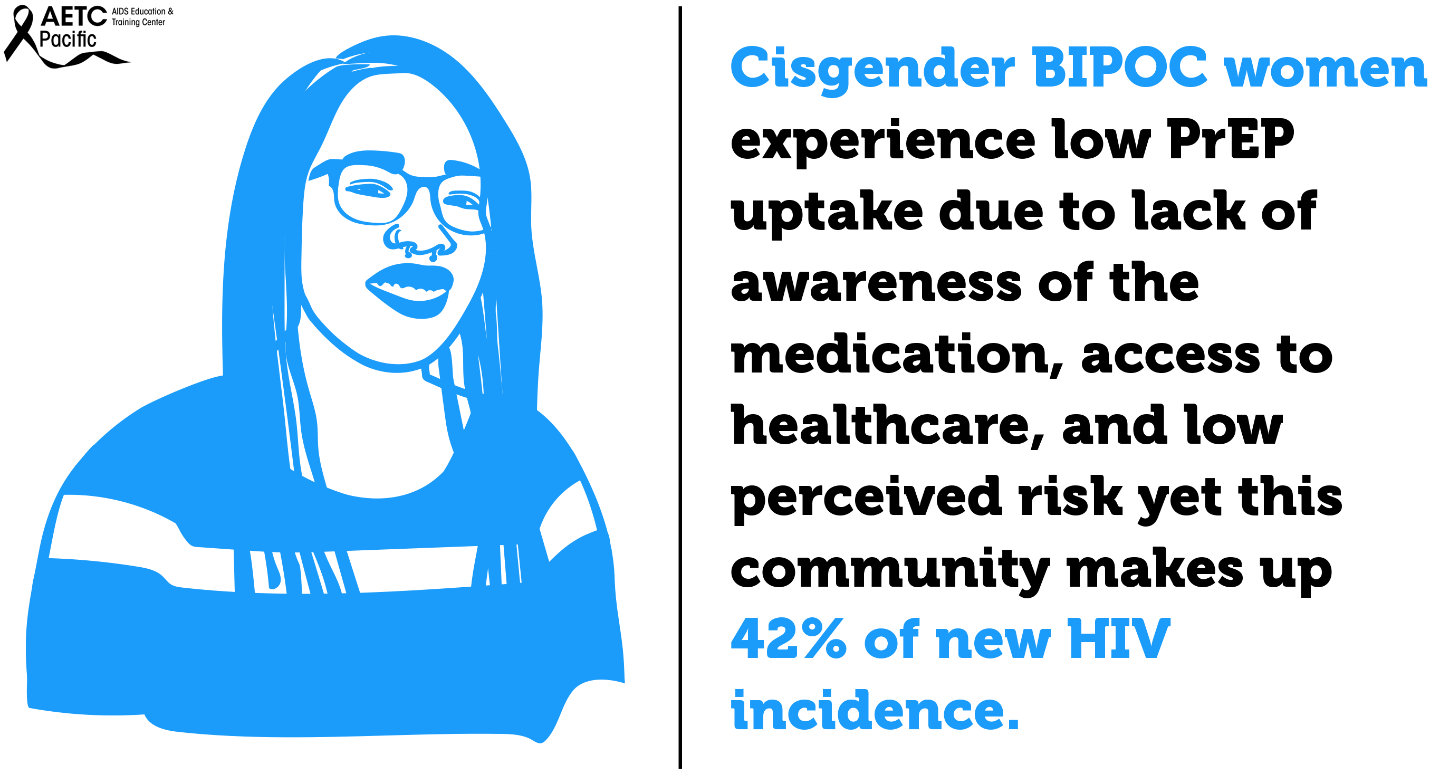

While African Americans only make up 13% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 42% of the 37,832 new HIV diagnoses in 2018, the highest rate among all racial and ethnic groups. Black women accounted for 57% of the new HIV diagnoses among women. Most new HIV diagnoses among women are attributed to heterosexual contact (84%) followed by injection drug use (16%). Black/African American cisgender women continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. Challenges to successful PrEP implementation among ciswomen include lack of awareness, access to healthcare, insurance and out-of-pocket costs and low perceived risk.

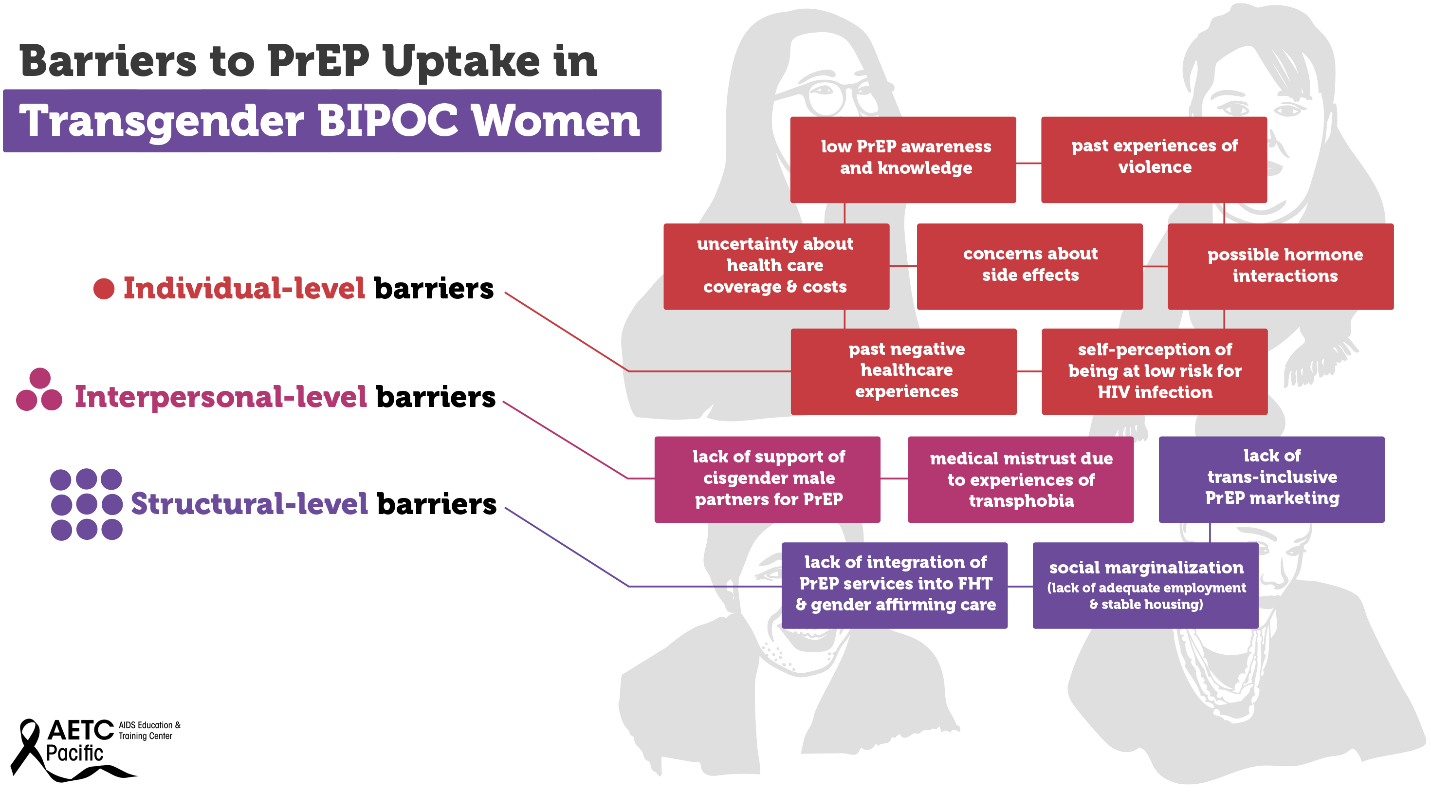

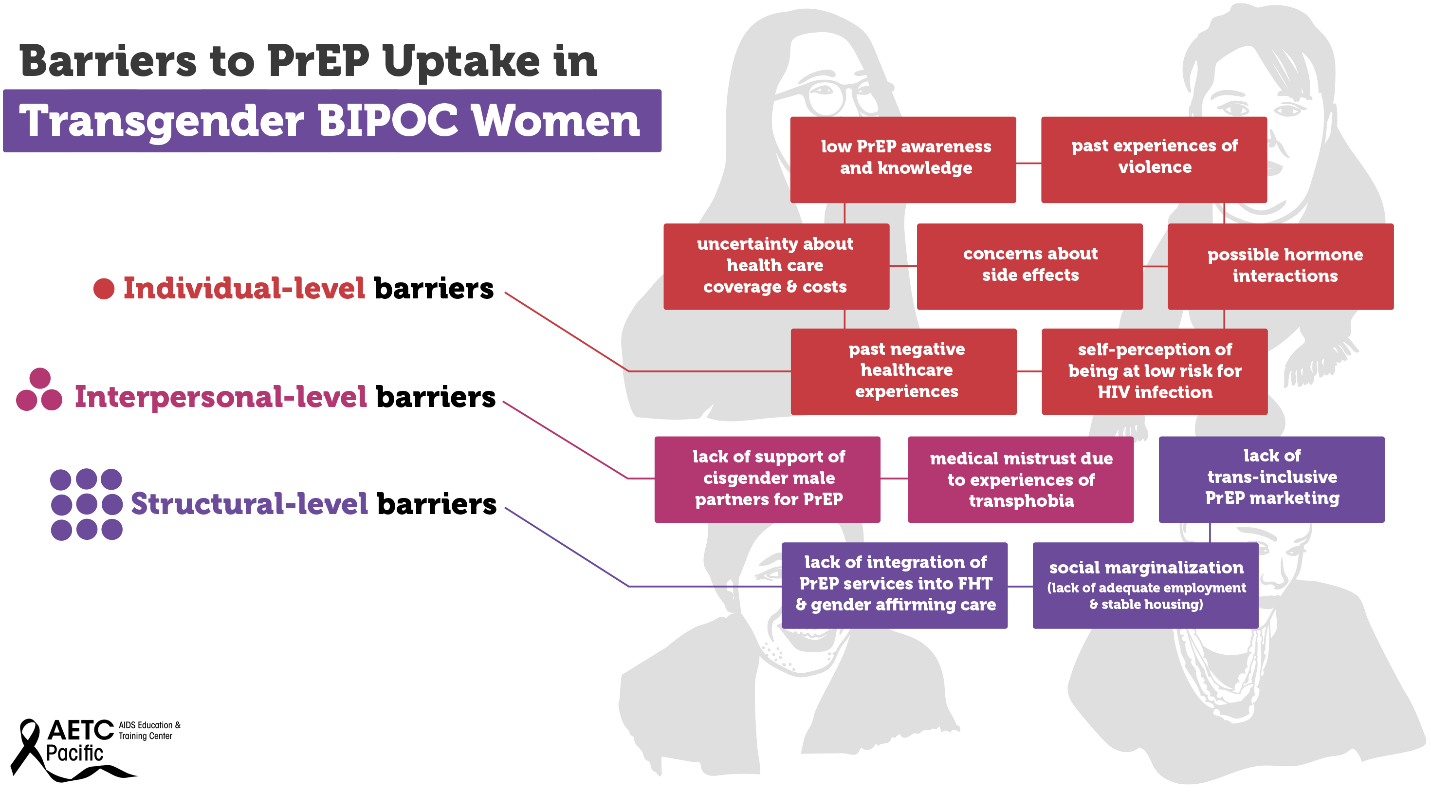

Transgender women—those who were assigned male at birth and who identity as female—are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the U.S. Between 2009 and 2014, an estimated 1,974 transgender women were diagnosed with HIV in the U.S., representing 84% of transgender people diagnosed. Racial and ethnic minority transgender women bear a higher burden of HIV compared to White transgender women. In the U.S., an estimated 44% of Black transgender women and 26% of Hispanic/Latina transgender women are living with HIV compared to 7% of White transgender women. Barriers to PrEP uptake among transgender women fall along multiple socio-ecological levels. Individual-level barriers may include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

Some examples of interpersonal-level barriers include lack of support of cisgender male partners for PrEP, and medical mistrust due to experiences of transphobia. Structural-level barriers include lack of trans-inclusive PrEP marketing, lack of integration of PrEP services into feminizing hormone therapy (FHT) and gender affirming care, and social marginalization (lack of adequate employment and stable housing). Experiences of social marginalization because of gender, class, race, sexual identity, poverty, and the intersection of these identities and experiences may contribute to increased vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Hispanic/Latina transgender women. Although several studies have investigated barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake among transgender women, there is a dearth of research on multilevel barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence specifically among Black and Hispanic/Latinx transgender women.

>

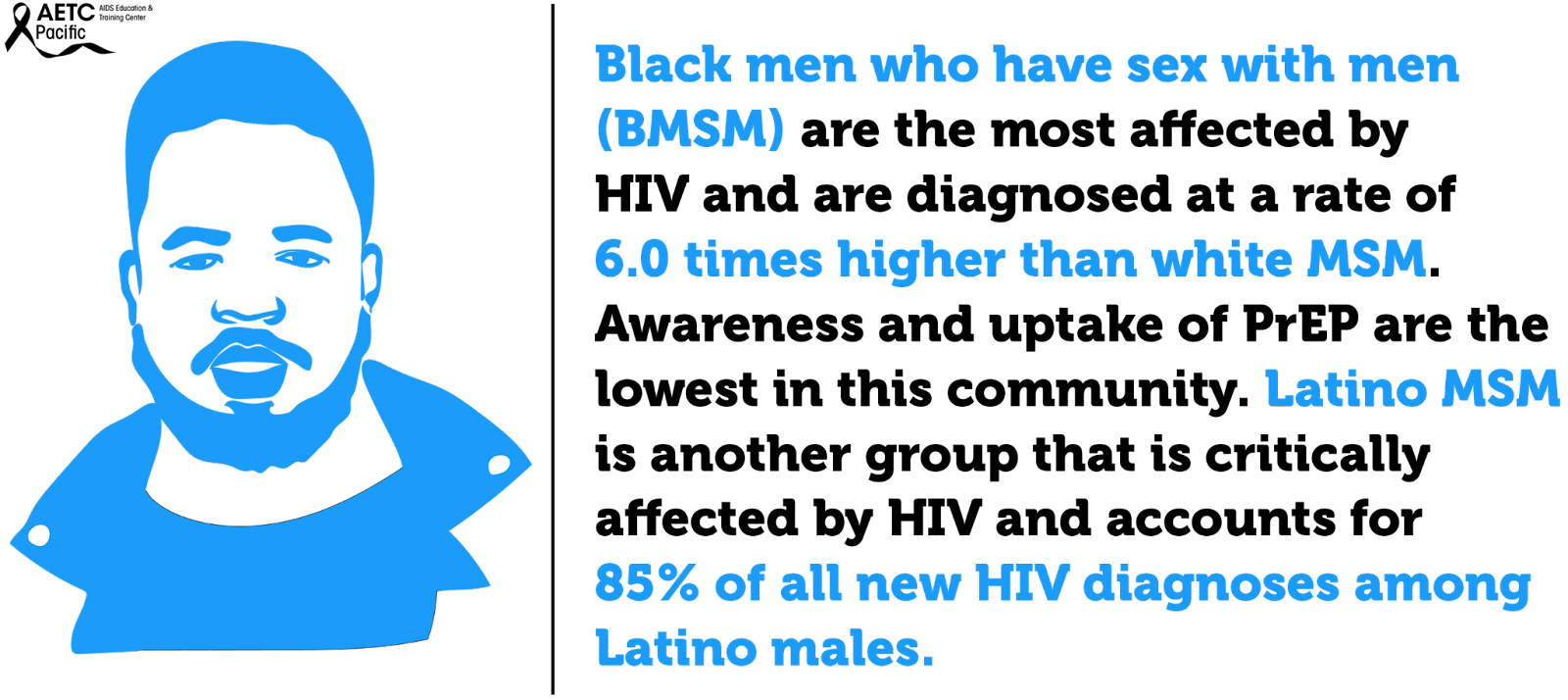

In the United States, Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) are the most affected by HIV and are diagnosed at a rate of 6.0 times higher than white MSM. Awareness and uptake of PrEP are lowest among this community. Latino MSM are another group that is critically affected by HIV and account for 85% of all new HIV diagnoses among Latino males. Like BMSM, barriers like cost and lack of insurance, concerns about side effects, societal or contextual factors such as racism and homophobia and HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs are barriers preventing Latino MSM from accessing PrEP.

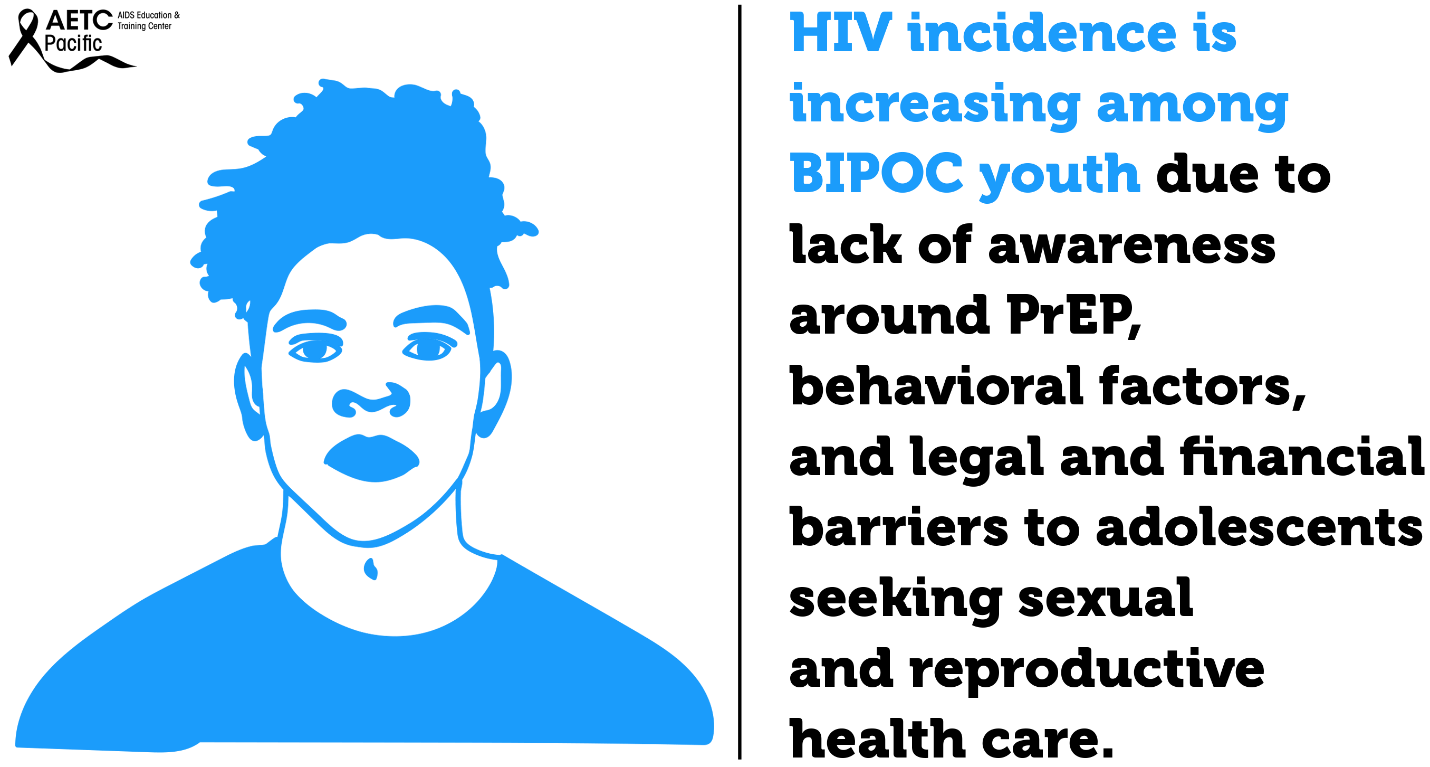

Youth continue to be a population impacted by higher rates of HIV. In 2019, 21% of new HIV diagnoses were among young people aged 13-24, and most of these cases are among Black and Latino youth. PrEP uptake among racial and ethnic minority adolescents has been slow due to lack of awareness of PrEP, behavioral factors, and legal and financial barriers to adolescents seeking sexual and reproductive health care.

Indian/Alaska Native adults and adolescents increased. Access to PrEP and PEP in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities can be limited and there are cultural and historical considerations that impact Tribal communities’ ability to adopt PrEP, and social and systematic considerations that also present challenges.

According to the CDC, Asian Americans who make up only 6 percent of the U.S. population, make up 2 percent of all HIV infections. The CDC suggests this disparity is so great due to cultural factors, such as language barriers and immigration issues that create barriers to accessing healthcare (though this only addresses access to care for Asian immigrants, not Asian Americans who have lived in the U.S. for generations.) Low PrEP utilization rates among the Asian/Pacific Islander communities could be because of lack of awareness about the medication, misconceptions regarding its affordability, misinformation about its effects and fear of community stigma about sex.

HIV incidence is high among people who use drugs and are unhoused across the U.S. This is fueled by the opioid epidemic, lack of affordable housing, socioeconomic marginalization, and other complex factors. Despite this, PrEP is largely under-utilized among this vulnerable population.

Some of the low PrEP uptake can be attributed to practical barriers, such as competing health and survival needs, and medications being lost or stolen due to being unhoused and without a safe place to store medications. However, there is also a pervasive belief among clinicians that people who use drugs who are unhoused are not good candidates for PrEP. This idea is likely due to overlapping stigmas and isn’t supported by data.

According to California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS, Substance Use Community engagement efforts have linked methamphetamine use to increased risk for HIV infection and falling out of medical care. County-specific data on methamphetamine use is not easily accessible. This CDPH report on Ending the HIV Epidemic utilizes county-specific data on 1) amphetamine-related Emergency Department (ED) visits and 2) amphetamine-related deaths 2011-2018; all data obtained from the California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard. From 2011-2013, there was an overall increase of ED visits attributable to amphetamine use in Alameda County, from 5.01 visits/100,000 population in 2011, to 5.81/100,000 in 2013. Since 2013, ED visits steadily declined to a low of 1.7/100,000 in 2018. Deaths, on the other hand, fluctuated more widely, from a low of 1.18/100,000 in 2011 to a high of 4/100,000 in 2013.

However, in 2018, deaths attributable to amphetamine use spiked dramatically to a high of 8.26/100,000. This spike, coming as ED visits continued to decline, may reflect persons not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose rather than decreased use. Not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose could be secondary to a lack of access to medical care, fear of legal ramifications, or to unwitnessed overdose— the reasons are unclear from this data.

Why Are We Doing So Poorly?

National HIV screening recommendations place healthcare providers at the helm in the fight against HIV. While the goal of healthcare providers should be to ensure high quality HIV prevention for patients, their stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward vulnerable populations impede progress in identifying patients who would benefit from PrEP. Some of the assumptions that clinicians make about patients seeking PrEP accompany and may exacerbate systemic factors affecting PrEP uptake, like patients’ distrust, lack of access to care, and lack of awareness of PrEP. One of the key reasons cited for clinicians not prescribing PrEP is their assumption that patients will not be adherent to PrEP followed by assumptions that patients taking PrEP will increase their frequency of condomless sex or number of sexual partners.

What is Medical Mistrust?

Medical Mistrust is “an absence of trust that health care providers and organizations genuinely care for patients’ interests, are honest, practice confidentiality, and have the competence to produce the best possible results.”

The Origins of Medical Mistrust

Research indicates that Medical Mistrust is rooted in the history of mistreatment, discrimination, and abuse perpetrated against Black and brown bodies, sexual and gender diverse people, and other marginalized groups by both the State and the medical establishment. In addition, contemporary experiences of discrimination in health such as inequities in access to medical insurance, health care facilities, and treatments along with institutional practices that make it difficult for marginalized communities to access quality health care also play a significant role in shaping Medical Mistrust particularly among Black and other patients of color. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

The Impact of Medical Mistrust

- Trust in health care among Americans has declined in recent decades

- Mistrust may prevent people from seeking care

- Black Americans are more likely than whites to say they do not trust their medical provider

- People who say they mistrust health care organizations are less likely to take medical advice, keep follow-up appointments, or fill prescriptions

- People who say they mistrust health care systems are more likely to report being in poor health

Talking with Patients about Medical Mistrust – How to Have Those Conversations

In the U.S., trust in the health care system is extremely low. Reversing medical mistrust is integral to building and strengthening patient-provider relationships. Health care professionals should assume patient mistrust and take the appropriate steps to address it.

Effective ways to communicate with patients about Medical Mistrust

- Openly discuss mistrust with patients

- Talk with, not at patients

- Partner with patients in making decisions about their health care

Medical mistrust has been identified as a primary driver of racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes in the U.S. Among Black individuals, medical mistrust stems from experiences with discrimination in healthcare and is the result of persistent social inequity and structural racism, both contemporary and historical. Regarding PrEP use, several studies have identified medical mistrust as a barrier to uptake among Black individuals. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

Medical mistrust is a major barrier to a strong patient-clinician relationship. Patient mistrust in health care clinicians and in the health care system generally, negatively influences patient behavior and health outcomes.

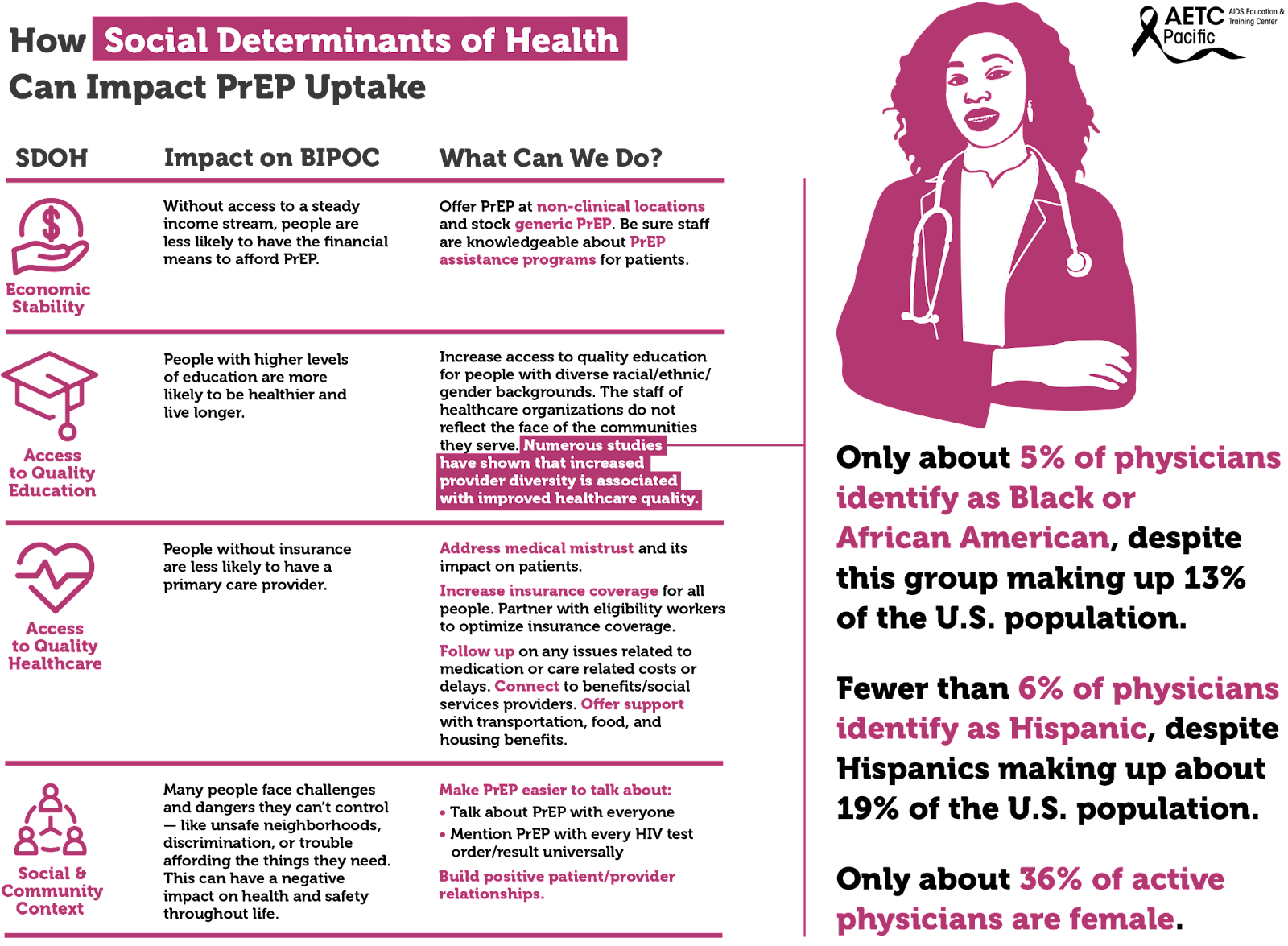

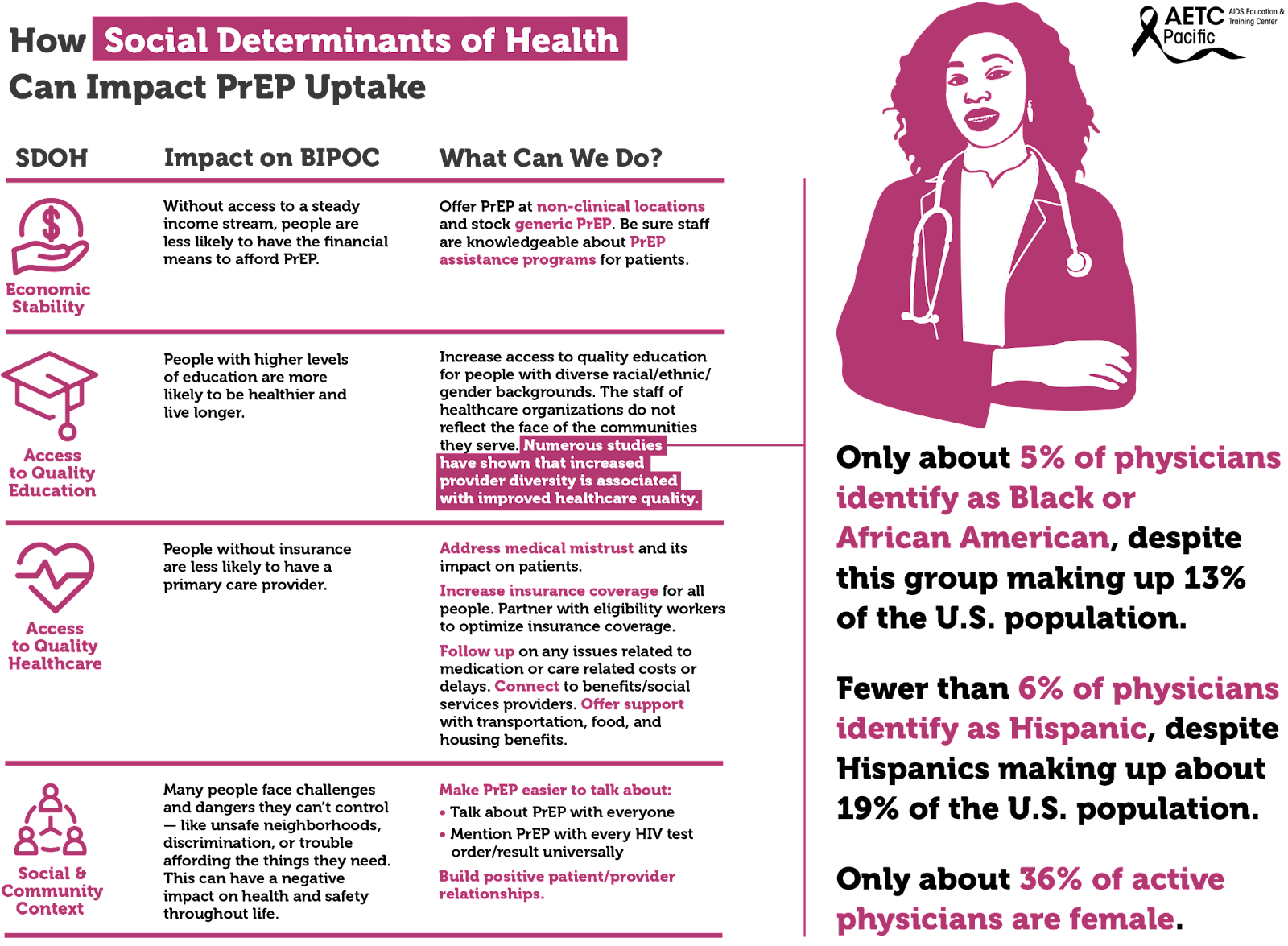

Furthermore, the staff of healthcare organizations do not reflect the face of the communities they serve. Numerous studies have shown that increased provider diversity is associated with improved healthcare quality. Concordant care, defined as a patient and provider sharing a common attribute such as race, ethnicity, or gender, has been associated with improved quality of care. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, only about 36% of active physicians are female, and only about 5% of physicians identify as Black or African-American, despite this group making up 13% of the U.S. population. Fewer than 6% of physicians identify as Hispanic, despite Hispanics making up about 19% of the U.S. population. However, 28% of physicians and surgeons in the United States are immigrants, with doctors from India and China making up the largest groups. This speaks to issues of systemic oppression: People from minority groups that have been oppressed for generations in the United States are less represented as physicians than are immigrants of color. There is a long history related to how we have gotten here. Since Abraham Flexner’s review of the American medical education system in 1910, it was believed that there was a limited role for Black physicians in the medical community and that Black physicians possessed less potential and ability than their White counterparts. The result of this characterization led to the closure of five of seven African American medical schools. The impact is still felt today.

Social determinants of health, the conditions in environments where people live, drive inequities, HIV acquisition and the use of PrEP among BIPOC. These social determinants include, among others, economic stability, access to quality education, and access to quality healthcare.

The uptake of PrEP has been shown to be impacted by unmet social determinants of health (SDOH) needs. These include basic needs (e.g., food, shelter, water), health/social service needs (e.g., healthcare), and economic needs (e.g., money for savings). Socioeconomic factors identified to affect PrEP uptake included lack of insurance, difficult access to transportation, and inflexible work situations. Individuals with more unmet SDOH needs may have other priorities that divert their focus from obtaining preventative health services.

There are multiple socioeconomic factors to consider when looking at the barriers to PrEP uptake among disproportionately impacted communities at both the individual-level and structural-level barriers. Individual-level barriers to PrEP uptake include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

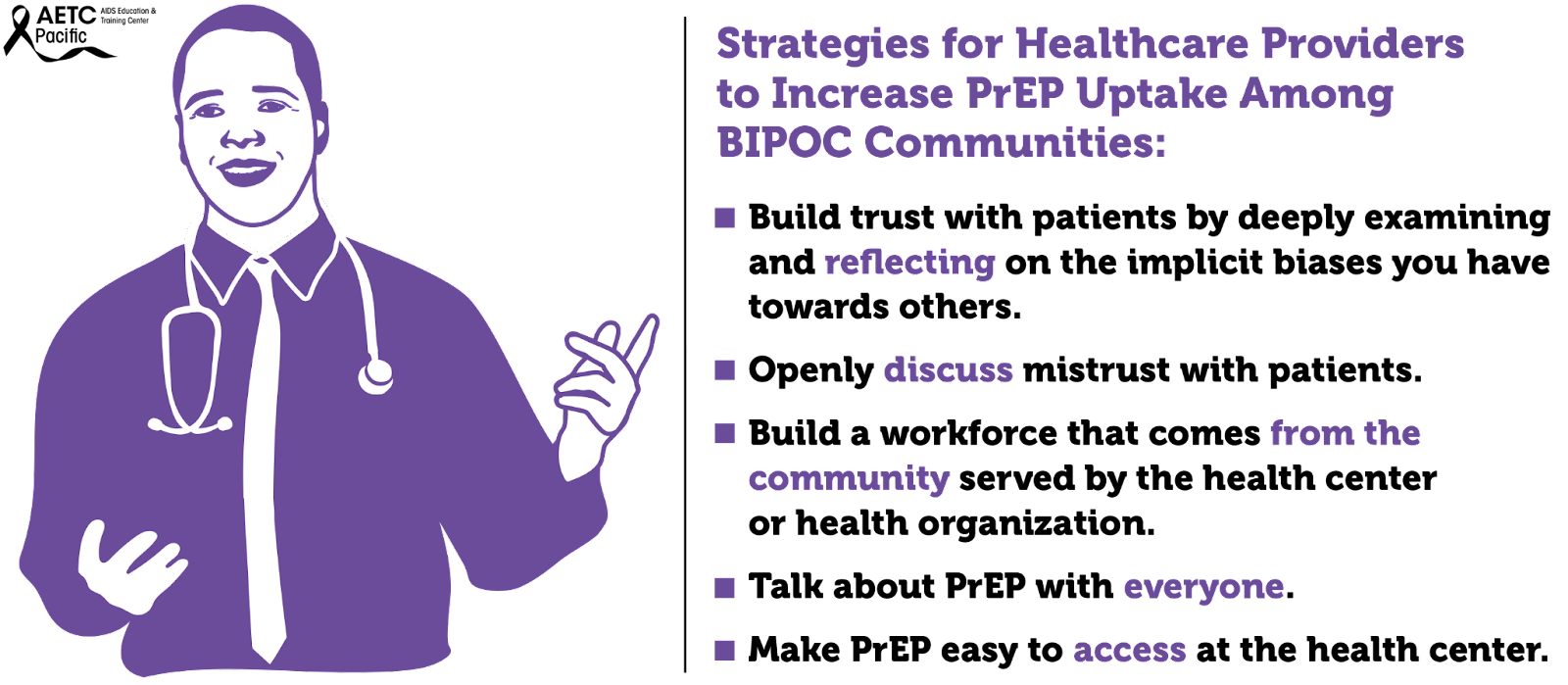

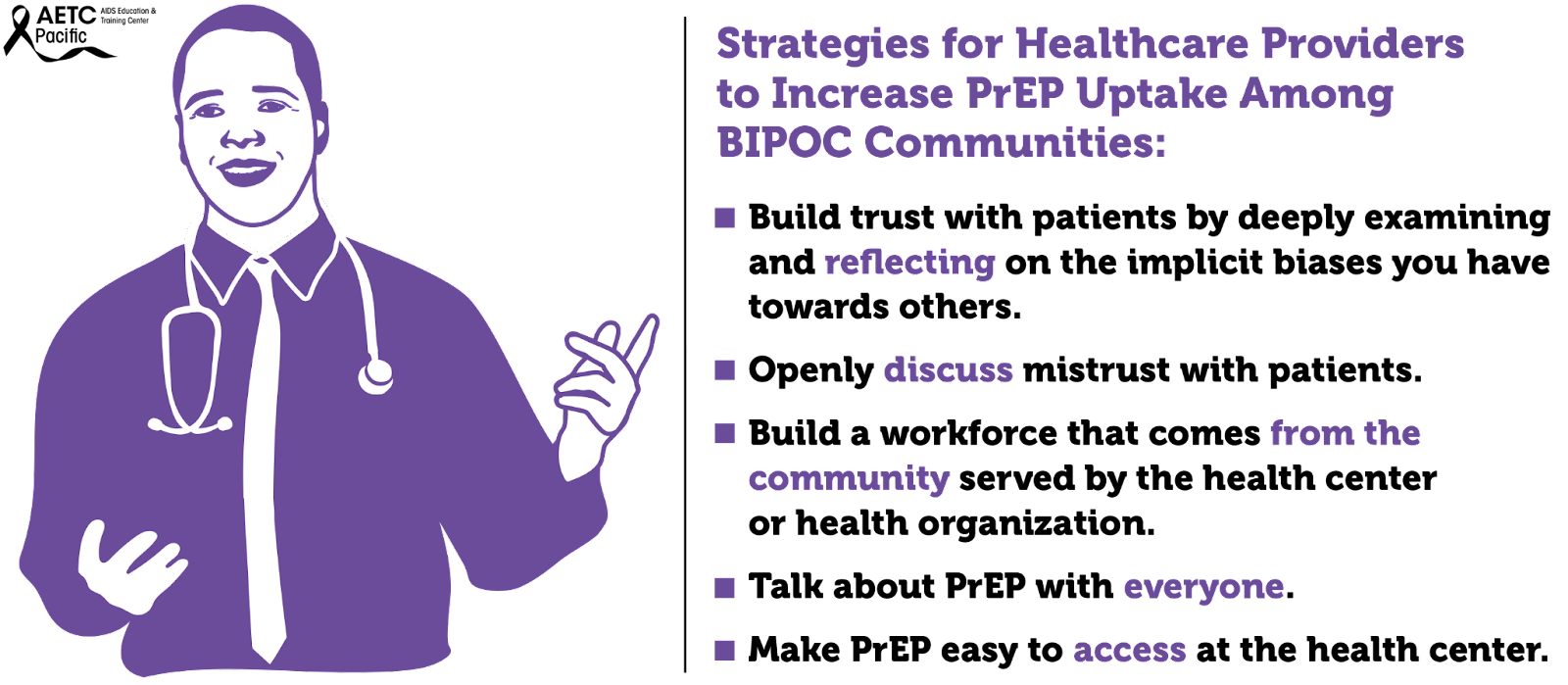

What providers can do to improve PrEP utilization among BIPOC people?

- Prior to meeting your patient:

- Check your bias and personal story: what baggage do you bring to the table?

- Look at their chart to get a sense of who they are

- Beware of microaggressions

- Don’t speak in generalities

- Don’t assume race/ethnicity

- Don’t assume gender/sexual identity

- Don’t assume pop culture references

- Condescension while being questioned

- What to bring to the patient interaction?

- Any member of the care team (e.g., PrEP Navigator, Case Manager) can learn about the familial context and/or patient’s culture and share what they learn with the provider and/or providers can build rapport by expressing an interest in learning about these aspects of the patient's life as they get to know each other

- Questions around culture

- Familial Context

- Learn about the familial responsibilities of the patient

- Learn about the patient’s biological/chosen support system

- Ask about personal & familial experience with health insurance

- Ensure prescriptions are affordable within the patient’s budget

- Discuss ease of getting to your clinic

- Discuss ease of physically accessing referral care and/or pharmacies

- Words Matter

- Providers can utilize a mutually agreed-upon opening script within the clinic about how to frame these questions. An example could be: "I'm interested in learning about how we can support you now or in the future" or "it's important to me to know if there are any issues that are coming up even if I can't help right away"

- It is not “dumbing-down” to speak to patients in a culturally-responsive manner

- If you do not speak their vernacular, learn

- If you misspeak & offend, apologize

- Watch for “Why” questions: instead of asking “Why do you want to take PrEP?” or “why don’t you use condoms,” you can ask “Tell me about what makes you want to take PrEP” or “Tell me about how you make decisions about condoms”

- Do not ask: “Do you understand?”

- Ask: “Please tell me what you think I said. It is important that we are on the same page.”

- Support Resilience

- It is important to “reframe the misconception to see [Black LGBTQ people] as “at risk” and instead see them as “at promise” for a future of good health and well-being anchored in their own resilience and supported by our abilities as staff, providers, and institutions to provide services to contribute to their resilience.”

- Consider exploring strengths and coping strategies by asking: What do you love about yourself? What has helped you to keep going even when times are hard? How can I best help you as you start PrEP?

- Care to Treatment

- Take time to address fears about a particular drug, pharmaceutical company, or the healthcare industrial complex. Take care not to argue a point, but rather to hear their perspective/concerns, then ask for permission to share additional information or your experience as a clinician, if appropriate.

- Storytelling of other patients’ experiences with medication is key for trust

- Share personal experience when appropriate, this is critical when recommending preventative care

- Be transparent if you or your clinic have been involved with any clinical trials or are receiving funding from pharmaceutical companies

- Create a safe & welcoming clinic

- Staff Diversity

- Actively engage clinic leadership to champion Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Anti-Racism efforts.

- Hire and retain staff that reflect the patient population, especially clinicians

- Encourage clinic leadership (including Human Resources) to adopt workplace policies, procedures, and compensation rates that foster retention of a culturally concordant workforce.

- Speak with staff and conduct quarterly trainings on cultural responsiveness.

- Have inclusive imagery and signs visible.

- Have BIPOC-centric brochures & magazines in waiting areas

- Post a Diversity & Inclusion statement in a conspicuous location

- Bringing them back to care

- Before the patient leaves the visit:

- Confirm the best form of future contact

- If you have a portal, make sure that it is on their mobile phone

- Ask them to send you a Test Message

- Introduce them to the person(s) who may follow-up

- Patients, clients, customers may come once, but maybe not again

- Look at your client-level data and see if your BIPOC clients are coming back for their appointments

- It’s probably not them … It may just be you (and/or your staff)

- Conduct an anonymous survey of patients

- Be committed to receiving feedback and change

- Reiterate that you are committed to their success

- Ask for a verbal report card before the patient leaves

Address Social Determinants of Health whenever possible. One of the findings in a PrEP navigation study highlights the benefit of offering clinical and non-clinical PrEP services to clients in one place which facilitates clients’ access to PrEP services. A co-located approach can ameliorate barriers such as time constraints, PrEP cost and lack of insurance, and low/limited income. This is particularly important when there is a low PrEP uptake among racial and gender minorities who are disproportionately affected by HIV.

- Hire a PrEP Navigator or train community health workers in PrEP Navigation

- Partner with eligibility workers to optimize insurance coverage

- Support with transportation benefits

- Connect to food and housing resources

- Connect to benefits/social services providers

- Follow up on any issues related to medication or care related costs or delays

Make PrEP easier to talk about:

- Talk about PrEP with everyone.

- Mention PrEP with every HIV test order/result universally.

- Make PrEP easier for patients to get:

- Stock generic PrEP and use it as first line agent (cost-effective).

- Offer tele-prep follow-up as an option.

- Do not withhold next prescriptions due to missed appointment (as long as the HIV test is complete and negative).

Offer options:

- Consider offering a 1-month follow-up if the patient is ambivalent or unsure about adherence (before extending to every 3 month visits).

- Honor choice: Continue to offer all tools in the HIV prevention toolkit even if it’s not the provider’s preference.

- If patient is not ready for sexual history discussion on first visit, that’s ok. Revisit this discussion at next appointment or when rapport is built.

- Greater than AIDS PrEP campaign “Powered by PrEP”: POC centered messaging including testimonials in English and Spanish

- REACH LA’s WAP campaign

- Black AIDS Institute: black cis women

- Cardea: HIV Care for Native patients

- Labeling transwomen as MSM

- MSM of color - Leo Moore presentation

- People of trans experience - evidence of lack of interaction with gender-affirming hormones

- Reproductive health - evidence of safety in conceiving, pregnancy & lactation. (HIVE toolkit)

- Seicus PrEP Education for Youth-Serving Primary Care Providers Toolkit

- Lack of diversity in healthcare Infographic

- National LGBT Health Education Center: “Understanding and Addressing the Social Determinants of Health for Black LGBTQ People”

- Same-day Oral PrEP quick guide: https://www.ebgtz.org/resource/same-day-prep/

Barriers to PrEP Faced by Communities Disproportionately Impacted by HIV

While African Americans only make up 13% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 42% of the 37,832 new HIV diagnoses in 2018, the highest rate among all racial and ethnic groups. Black women accounted for 57% of the new HIV diagnoses among women. Most new HIV diagnoses among women are attributed to heterosexual contact (84%) followed by injection drug use (16%). Black/African American cisgender women continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. Challenges to successful PrEP implementation among ciswomen include lack of awareness, access to healthcare, insurance and out-of-pocket costs and low perceived risk.

Transgender women—those who were assigned male at birth and who identity as female—are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the U.S. Between 2009 and 2014, an estimated 1,974 transgender women were diagnosed with HIV in the U.S., representing 84% of transgender people diagnosed. Racial and ethnic minority transgender women bear a higher burden of HIV compared to White transgender women. In the U.S., an estimated 44% of Black transgender women and 26% of Hispanic/Latina transgender women are living with HIV compared to 7% of White transgender women. Barriers to PrEP uptake among transgender women fall along multiple socio-ecological levels. Individual-level barriers may include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

Some examples of interpersonal-level barriers include lack of support of cisgender male partners for PrEP, and medical mistrust due to experiences of transphobia. Structural-level barriers include lack of trans-inclusive PrEP marketing, lack of integration of PrEP services into feminizing hormone therapy (FHT) and gender affirming care, and social marginalization (lack of adequate employment and stable housing). Experiences of social marginalization because of gender, class, race, sexual identity, poverty, and the intersection of these identities and experiences may contribute to increased vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Hispanic/Latina transgender women. Although several studies have investigated barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake among transgender women, there is a dearth of research on multilevel barriers to PrEP uptake and adherence specifically among Black and Hispanic/Latinx transgender women.

>

In the United States, Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) are the most affected by HIV and are diagnosed at a rate of 6.0 times higher than white MSM. Awareness and uptake of PrEP are lowest among this community. Latino MSM are another group that is critically affected by HIV and account for 85% of all new HIV diagnoses among Latino males. Like BMSM, barriers like cost and lack of insurance, concerns about side effects, societal or contextual factors such as racism and homophobia and HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs are barriers preventing Latino MSM from accessing PrEP.

Youth continue to be a population impacted by higher rates of HIV. In 2019, 21% of new HIV diagnoses were among young people aged 13-24, and most of these cases are among Black and Latino youth. PrEP uptake among racial and ethnic minority adolescents has been slow due to lack of awareness of PrEP, behavioral factors, and legal and financial barriers to adolescents seeking sexual and reproductive health care.

Indian/Alaska Native adults and adolescents increased. Access to PrEP and PEP in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities can be limited and there are cultural and historical considerations that impact Tribal communities’ ability to adopt PrEP, and social and systematic considerations that also present challenges.

According to the CDC, Asian Americans who make up only 6 percent of the U.S. population, make up 2 percent of all HIV infections. The CDC suggests this disparity is so great due to cultural factors, such as language barriers and immigration issues that create barriers to accessing healthcare (though this only addresses access to care for Asian immigrants, not Asian Americans who have lived in the U.S. for generations.) Low PrEP utilization rates among the Asian/Pacific Islander communities could be because of lack of awareness about the medication, misconceptions regarding its affordability, misinformation about its effects and fear of community stigma about sex.

HIV incidence is high among people who use drugs and are unhoused across the U.S. This is fueled by the opioid epidemic, lack of affordable housing, socioeconomic marginalization, and other complex factors. Despite this, PrEP is largely under-utilized among this vulnerable population.

Some of the low PrEP uptake can be attributed to practical barriers, such as competing health and survival needs, and medications being lost or stolen due to being unhoused and without a safe place to store medications. However, there is also a pervasive belief among clinicians that people who use drugs who are unhoused are not good candidates for PrEP. This idea is likely due to overlapping stigmas and isn’t supported by data.

According to California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS, Substance Use Community engagement efforts have linked methamphetamine use to increased risk for HIV infection and falling out of medical care. County-specific data on methamphetamine use is not easily accessible. This CDPH report on Ending the HIV Epidemic utilizes county-specific data on 1) amphetamine-related Emergency Department (ED) visits and 2) amphetamine-related deaths 2011-2018; all data obtained from the California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard. From 2011-2013, there was an overall increase of ED visits attributable to amphetamine use in Alameda County, from 5.01 visits/100,000 population in 2011, to 5.81/100,000 in 2013. Since 2013, ED visits steadily declined to a low of 1.7/100,000 in 2018. Deaths, on the other hand, fluctuated more widely, from a low of 1.18/100,000 in 2011 to a high of 4/100,000 in 2013.

However, in 2018, deaths attributable to amphetamine use spiked dramatically to a high of 8.26/100,000. This spike, coming as ED visits continued to decline, may reflect persons not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose rather than decreased use. Not seeking medical care for amphetamine overdose could be secondary to a lack of access to medical care, fear of legal ramifications, or to unwitnessed overdose— the reasons are unclear from this data.

Why Are We Doing So Poorly?

National HIV screening recommendations place healthcare providers at the helm in the fight against HIV. While the goal of healthcare providers should be to ensure high quality HIV prevention for patients, their stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward vulnerable populations impede progress in identifying patients who would benefit from PrEP. Some of the assumptions that clinicians make about patients seeking PrEP accompany and may exacerbate systemic factors affecting PrEP uptake, like patients’ distrust, lack of access to care, and lack of awareness of PrEP. One of the key reasons cited for clinicians not prescribing PrEP is their assumption that patients will not be adherent to PrEP followed by assumptions that patients taking PrEP will increase their frequency of condomless sex or number of sexual partners.

What is Medical Mistrust?

Medical Mistrust is “an absence of trust that health care providers and organizations genuinely care for patients’ interests, are honest, practice confidentiality, and have the competence to produce the best possible results.”

The Origins of Medical Mistrust

Research indicates that Medical Mistrust is rooted in the history of mistreatment, discrimination, and abuse perpetrated against Black and brown bodies, sexual and gender diverse people, and other marginalized groups by both the State and the medical establishment. In addition, contemporary experiences of discrimination in health such as inequities in access to medical insurance, health care facilities, and treatments along with institutional practices that make it difficult for marginalized communities to access quality health care also play a significant role in shaping Medical Mistrust particularly among Black and other patients of color. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

The Impact of Medical Mistrust

- Trust in health care among Americans has declined in recent decades

- Mistrust may prevent people from seeking care

- Black Americans are more likely than whites to say they do not trust their medical provider

- People who say they mistrust health care organizations are less likely to take medical advice, keep follow-up appointments, or fill prescriptions

- People who say they mistrust health care systems are more likely to report being in poor health

Talking with Patients about Medical Mistrust – How to Have Those Conversations

In the U.S., trust in the health care system is extremely low. Reversing medical mistrust is integral to building and strengthening patient-provider relationships. Health care professionals should assume patient mistrust and take the appropriate steps to address it.

Effective ways to communicate with patients about Medical Mistrust

- Openly discuss mistrust with patients

- Talk with, not at patients

- Partner with patients in making decisions about their health care

Medical mistrust has been identified as a primary driver of racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes in the U.S. Among Black individuals, medical mistrust stems from experiences with discrimination in healthcare and is the result of persistent social inequity and structural racism, both contemporary and historical. Regarding PrEP use, several studies have identified medical mistrust as a barrier to uptake among Black individuals. Studies that have explored healthcare experiences among different populations have identified a significant association between race and medical mistrust such that Black Americans are significantly more likely than White Americans to mistrust healthcare personnel and the medical system as a whole.

Medical mistrust is a major barrier to a strong patient-clinician relationship. Patient mistrust in health care clinicians and in the health care system generally, negatively influences patient behavior and health outcomes.

Furthermore, the staff of healthcare organizations do not reflect the face of the communities they serve. Numerous studies have shown that increased provider diversity is associated with improved healthcare quality. Concordant care, defined as a patient and provider sharing a common attribute such as race, ethnicity, or gender, has been associated with improved quality of care. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, only about 36% of active physicians are female, and only about 5% of physicians identify as Black or African-American, despite this group making up 13% of the U.S. population. Fewer than 6% of physicians identify as Hispanic, despite Hispanics making up about 19% of the U.S. population. However, 28% of physicians and surgeons in the United States are immigrants, with doctors from India and China making up the largest groups. This speaks to issues of systemic oppression: People from minority groups that have been oppressed for generations in the United States are less represented as physicians than are immigrants of color. There is a long history related to how we have gotten here. Since Abraham Flexner’s review of the American medical education system in 1910, it was believed that there was a limited role for Black physicians in the medical community and that Black physicians possessed less potential and ability than their White counterparts. The result of this characterization led to the closure of five of seven African American medical schools. The impact is still felt today.

Social determinants of health, the conditions in environments where people live, drive inequities, HIV acquisition and the use of PrEP among BIPOC. These social determinants include, among others, economic stability, access to quality education, and access to quality healthcare.

The uptake of PrEP has been shown to be impacted by unmet social determinants of health (SDOH) needs. These include basic needs (e.g., food, shelter, water), health/social service needs (e.g., healthcare), and economic needs (e.g., money for savings). Socioeconomic factors identified to affect PrEP uptake included lack of insurance, difficult access to transportation, and inflexible work situations. Individuals with more unmet SDOH needs may have other priorities that divert their focus from obtaining preventative health services.

There are multiple socioeconomic factors to consider when looking at the barriers to PrEP uptake among disproportionately impacted communities at both the individual-level and structural-level barriers. Individual-level barriers to PrEP uptake include low PrEP awareness and knowledge, past experiences of violence, uncertainty about health insurance coverage and associated health costs, concerns about side effects, possible hormone interactions, past negative healthcare experiences, and self-perception of being at low risk for HIV infection.

What Providers Can Do To Improve PrEP Utilization Among BIPOC People?

- Prior to meeting your patient:

- Check your bias and personal story: what baggage do you bring to the table?

- Look at their chart to get a sense of who they are

- Beware of microaggressions

- Don’t speak in generalities

- Don’t assume race/ethnicity

- Don’t assume gender/sexual identity

- Don’t assume pop culture references

- Condescension while being questioned

- What to bring to the patient interaction?

- Any member of the care team (e.g., PrEP Navigator, Case Manager) can learn about the familial context and/or patient’s culture and share what they learn with the provider and/or providers can build rapport by expressing an interest in learning about these aspects of the patient's life as they get to know each other

- Questions around culture

- Familial Context

- Learn about the familial responsibilities of the patient

- Learn about the patient’s biological/chosen support system

- Ask about personal & familial experience with health insurance

- Ensure prescriptions are affordable within the patient’s budget

- Discuss ease of getting to your clinic

- Discuss ease of physically accessing referral care and/or pharmacies

- Words Matter

- Providers can utilize a mutually agreed-upon opening script within the clinic about how to frame these questions. An example could be: "I'm interested in learning about how we can support you now or in the future" or "it's important to me to know if there are any issues that are coming up even if I can't help right away"

- It is not “dumbing-down” to speak to patients in a culturally-responsive manner

- If you do not speak their vernacular, learn

- If you misspeak & offend, apologize

- Watch for “Why” questions: instead of asking “Why do you want to take PrEP?” or “why don’t you use condoms,” you can ask “Tell me about what makes you want to take PrEP” or “Tell me about how you make decisions about condoms”

- Do not ask: “Do you understand?”

- Ask: “Please tell me what you think I said. It is important that we are on the same page.”

- Support Resilience

- It is important to “reframe the misconception to see [Black LGBTQ people] as “at risk” and instead see them as “at promise” for a future of good health and well-being anchored in their own resilience and supported by our abilities as staff, providers, and institutions to provide services to contribute to their resilience.”

- Consider exploring strengths and coping strategies by asking: What do you love about yourself? What has helped you to keep going even when times are hard? How can I best help you as you start PrEP?

- Care to Treatment

- Take time to address fears about a particular drug, pharmaceutical company, or the healthcare industrial complex. Take care not to argue a point, but rather to hear their perspective/concerns, then ask for permission to share additional information or your experience as a clinician, if appropriate.

- Storytelling of other patients’ experiences with medication is key for trust

- Share personal experience when appropriate, this is critical when recommending preventative care

- Be transparent if you or your clinic have been involved with any clinical trials or are receiving funding from pharmaceutical companies

- Create a safe & welcoming clinic

- Staff Diversity

- Actively engage clinic leadership to champion Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Anti-Racism efforts.

- Hire and retain staff that reflect the patient population, especially clinicians

- Encourage clinic leadership (including Human Resources) to adopt workplace policies, procedures, and compensation rates that foster retention of a culturally concordant workforce.

- Speak with staff and conduct quarterly trainings on cultural responsiveness.

- Have inclusive imagery and signs visible.

- Have BIPOC-centric brochures & magazines in waiting areas

- Post a Diversity & Inclusion statement in a conspicuous location

- Bringing them back to care

- Before the patient leaves the visit:

- Confirm the best form of future contact

- If you have a portal, make sure that it is on their mobile phone

- Ask them to send you a Test Message

- Introduce them to the person(s) who may follow-up

- Patients, clients, customers may come once, but maybe not again

- Look at your client-level data and see if your BIPOC clients are coming back for their appointments

- It’s probably not them … It may just be you (and/or your staff)

- Conduct an anonymous survey of patients

- Be committed to receiving feedback and change

- Reiterate that you are committed to their success

- Ask for a verbal report card before the patient leaves

Address Social Determinants of Health whenever possible. One of the findings in a PrEP navigation study highlights the benefit of offering clinical and non-clinical PrEP services to clients in one place which facilitates clients’ access to PrEP services. A co-located approach can ameliorate barriers such as time constraints, PrEP cost and lack of insurance, and low/limited income. This is particularly important when there is a low PrEP uptake among racial and gender minorities who are disproportionately affected by HIV.

- Hire a PrEP Navigator or train community health workers in PrEP Navigation

- Partner with eligibility workers to optimize insurance coverage

- Support with transportation benefits

- Connect to food and housing resources

- Connect to benefits/social services providers

- Follow up on any issues related to medication or care related costs or delays

Make PrEP easier to talk about:

- Talk about PrEP with everyone.

- Mention PrEP with every HIV test order/result universally.

- Make PrEP easier for patients to get:

- Stock generic PrEP and use it as first line agent (cost-effective).

- Offer tele-prep follow-up as an option.

- Do not withhold next prescriptions due to missed appointment (as long as the HIV test is complete and negative).

Offer options:

- Consider offering a 1-month follow-up if the patient is ambivalent or unsure about adherence (before extending to every 3 month visits).

- Honor choice: Continue to offer all tools in the HIV prevention toolkit even if it’s not the provider’s preference.

- If patient is not ready for sexual history discussion on first visit, that’s ok. Revisit this discussion at next appointment or when rapport is built.

- Greater than AIDS PrEP campaign “Powered by PrEP”: POC centered messaging including testimonials in English and Spanish

- REACH LA’s WAP campaign

- Black AIDS Institute: black cis women

- Cardea: HIV Care for Native patients

- Labeling transwomen as MSM

- MSM of color - Leo Moore presentation

- People of trans experience - evidence of lack of interaction with gender-affirming hormones

- Reproductive health - evidence of safety in conceiving, pregnancy & lactation. (HIVE toolkit)

- Seicus PrEP Education for Youth-Serving Primary Care Providers Toolkit

- Lack of diversity in healthcare Infographic

- National LGBT Health Education Center: “Understanding and Addressing the Social Determinants of Health for Black LGBTQ People”

- Same-day Oral PrEP quick guide: https://www.ebgtz.org/resource/same-day-prep/

PrEP Background

We will begin reviewing PrEP by introducing the different medications that are available and covering their effectiveness. Echoing some of the trends that were mentioned under HIV epidemiology, this section will also work to highlight the inequities in PrEP delivery and how we can work to improve them.

We will begin reviewing PrEP by introducing the different medications that are available and covering their effectiveness. Echoing some of the trends that were mentioned under HIV epidemiology, this section will also work to highlight the inequities in PrEP delivery and how we can work to improve them.

Medications Available

PrEP encompasses a group of medications meant to be taken by someone who is HIV negative to prevent acquiring an HIV infection.

PRE = Before

EXPOSURE = Coming into potential contact with HIV

PROPHYLAXIS = Treatment to prevent an infection

There are three different medications available for PrEP. Brand names are provided in bold.

- Emtricitabine 200mg & tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300mg (F/TDF). Truvada

- - Oral tablet approved for PrEP use in July 2012

- Emtricitabine 200mg & tenofovir alafenamide 25mg (F/TAF). Descovy

- - Oral tablet approved for PrEP use in October 2019

- Cabotegravir 600mg in 3mL (CAB). Apretude

- - Intramuscular injection approved for PrEP use in December 2021

- - Cabotegravir 30mg is also available in an oral form called Vocabria. There is an optional oral lead-in for 30 days before starting the injectable form.

Effectiveness

The majority of existing PrEP studies have focused on the use of oral F/TDF (Truvada) to prevent sexual transmission of HIV in both assigned sexes (AMAB & AFAB), regardless of sexual orientation. (9)